Days 1-5 Christmas Jelly

Foreword

Most of these stories are true.

Others are the invention of my imagination.

They’re all from my journals or laptop.

Most of all, they’re from my heart.

I hope they move you.

Go ahead and laugh.

Cry.

Celebrate.

Believe.

Ponder.

Enjoy.

My wish is that Christmas Jelly makes this holiday season the deepest and most meaningful ever for you and your family.

In fact, I encourage you to use the stories as part of a family time each night in December.

There are thirty-two chapters. One for each day in December, and a lagniappe chapter for New Year’s Day.

Take your time. Like a jar of homemade jelly, these stories are best digested a few spoonfuls at a time.

Enjoy every bite.

Curt Iles

Dry Creek, Louisiana

DECEMBER 1

Chapter 1

Christmas Jelly

“The only true gift is a portion of yourself.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson.

With sweaty palms, I wheel my pickup onto Eleanor Andrews Road. I feel as if it’s the first week of fifth grade and I’m handing in the dreaded assignment, “What I did this past summer.”

Why am I nervous? I’m a man on a mission: delivering a Christmas tree to my favorite grade school teacher. I fell in love with Eleanor Andrews during my fifth-grade year at East Beauregard School. The year was 1967 and I was an eleven-year-old skinny country boy with big ears.

She was a legendary teacher who’d tutored two generations of Dry Creek and Sugartown children. Mrs. Andrews was from what we called the “Old School.” She had a well-deserved, fierce reputation for being stern and taking no gruff or lip off anyone.

Young teachers knew not to park in her space. Young students knew not to back-talk her. I saw several get a good shaking when they tried.

Everyone knew not to disturb her during her smoke break in the teacher’s lounge.

I quickly saw how rigid her classroom was. Everything was “down the line.” She was the captain of the ship, and no one questioned that.

The first week of class I witnessed what her former students called “the stare.”

Hands on hips.

Tongue in cheek.

Scowl on her face.

I knew the stare would stop a charging grizzly bear in its tracks and made up my mind to not be on the business end of it.

I also noticed something else: beneath that gruff exterior were warm, smiling eyes. She loved watching students learn and leading them into new knowledge.

I learned that Reykjavik was the capital of Iceland, and it was a long way from Dry Creek.

I learned about subject and verb agreement.

I learned for the first time about the heartbreak of love.

I learned to love writing, and my love of reading deepened. Being the mother of three rowdy boys, she had the knack of letting country boys know it was okay to enjoy books and learning.

And I learned to love Eleanor Andrews. During that year, 1967, she became my favorite teacher. Now, over thirty years later, she still is.

# # #

She’s been retired for over two decades and doesn’t venture out anymore.

Lives by herself. We call it being “homebound.”

There’s a wonderful conspiracy in Dry Creek of taking care of her. Former students take her shopping. Clean her house. Cut her firewood.

She’s determined not to go in a nursing home, and our community is determined that this final major wish of her life succeed.

During this season of her life, she sits among her beautiful garden flowers, carefully tended by her neighbors. She lives alone in her house surrounded by her flowers and memories of a life filled with teaching and touching lives.

This December morning I received the expected call. “Curt, when you get a chance, drop by. I’ve got something for you.”

“Do you want me to bring your tree?”

“Yes, I’m ready for it.”

I know that the best present of the season is now ready.

It’s time for Christmas Jelly.

Back in October, I tagged a special Christmas tree for her. Knowing her exact standards in a tree, I carefully selected the one I thought she’d like best. Holding my saw, I walked around it one more time making sure it was the right height, width, and color.

That’s why I’m nervous. I want her to approve of the tree. Even though I’m now assistant principal at the school where she taught, I’m once again in the fifth grade waiting to hand in that essay.

I remove the tree from the truck, shaking it for loose needles.

“Come on in. I’ve been waiting for you.” She greets me with that special smile I’ve known over the years. She makes me feel as if I’m the most important person in the world. That’s why she’s always been my favorite teacher.

She nods at the kitchen table. “I’ve got something for you.”

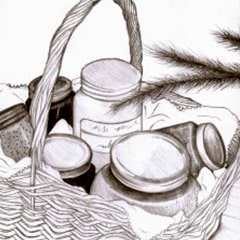

I see the basket full of colorful jars of homemade jelly.

Muscadine, mayhaw, even crabapple. Mixed in are jars of green pepper jelly, and tomato chow-chow. Topping it off is a Ziploc bag of her specialty candy: chocolate—“Martha Washington’s.”

My mouth waters at the thought of the hot biscuits the mayhaw jelly will top. The green pepper jelly will adorn a plate of purple hull peas. The chewy Martha Washington’s to be washed down with a cold glass of milk.

We visit over coffee in the manner that special friends do. We always seem to pick up right where we left off. That’s how the best friendships are.

After two more cups of coffee, I put her tree in its corner of honor. Nodding at her fireplace, I remind her to water it good.

“Curt, it’s the perfect tree.”

“You really like it?”

“It’s just right.” We now enter the next phase of this yearly ritual. She reaches for her purse. “How much do I owe you?’

“Nothing. The best deal I ever make is trading a tree for the best home-made jelly in Dry Creek.”

We hug and I leave with my armload of jelly jars and a lightened heart. At the end of Highway 113, I pause as a log truck roars by. Emerson’s quote comes back to me. “The only true gift is a portion of yourself.”

I touch the decorated jars and am reminded of what the spirit of Christmas is truly about.

It’s about giving.

Giving of ourselves.

Sharing what we have.

Giving handmade gifts that come from the heart.

I’m so glad I live in a place called Dry Creek.

A good place where gifts such as Christmas jelly abound.

DECEMBER 2

Chapter 2

My Grandpas’ Boots

Son, I notice you’re scowling at my scuffed boots. Like me, they’ve been around a while and have quite a story to tell. You’ll understand why I wear them proudly when I finish their tale.”

These boots are six years older than me, and I’m almost seventy. Their history goes back to the years after the Civil War. That war was hard on my hometown of Alexandria, Louisiana. General Banks and his retreating Union army left behind smoldering ruins in the spring of 1864.

My grandfather, Abram B. Terry, wasn’t there. He was a prisoner of war in a New York Union prison. When the war ended, he returned to Alexandria and the destruction he encountered deepened the bitterness he felt toward all things Yankee.

We called Grandpa Terry “Pops.” His only son, my father, was seven when Pops limped home from the war. He’d lost his left leg and replaced it with a stout dogwood crutch, and a heart that was harder than the hickory peg leg he now wore.

Pop’s full name was Abraham B. Terry. His first act on returning from the war was going to the courthouse and changing it to Abram B. Terry. He didn’t want any name that linked him with Lincoln, whom he personally blamed for the war.

# # #

Seventeen years after the end of the war—in the year 1882—Pops was still angry about it and the disaster it’d brought to the Red River cotton country. He disdainfully referred to the previous Reconstruction years as “Deconstruction.”

However, an event happened in the cold weeks before Christmas that year that changed his heart and our family’s destiny.

In the midst of this post-war economic vacuum, several Unionists bravely arrived in Alexandria. These so-called “carpetbaggers” were treated with scorn and suspicion.

Pop’s only son—my daddy—was now twenty-three and still single. Father and son operated a sawmill south of town. On this fateful day in December 1882, the two of them were going to the bank.

Pops, seeing a man wearing a faded Union greatcoat, said, “Hey Bluecoat, have you come back to see if there’s anything you didn’t burn the first time?”

The man, who was sitting at a checkerboard balanced on a whiskey keg, looked up with a disarming smile. “I don’t want to burn nothing. I might catch fire, too.” He lifted his right pants leg, revealing a wooden peg.

Pops squinted. “Where’d you lose that?”

“One of your snipers got it on the last day at Vicksburg. They say I was the final casualty.”

Pops leaned on his crutch revealing his own wooden leg. “Lost mine in ‘Pencil-vain-ya.’” He hobbled closer. “How far’s yours gone?”

“To the hip.”

Pops grimaced. “I guess I ought to be thankful for below the knee.”

“Mine started below the knee too, but Ol’ Sawbones just kept cutting.” Bluecoat winked. “Told him I’d shoot him if he went any higher.”

“Bluecoat, you lost your right laig.”

The man moved his checkerboard. “And I see you left your left one somewhere up north, Reb.”

“Yep, they buried it in a stump hole at Gettysburg. Pickett’s Charge. July 3rd, 1863.”

Bluecoat grinned. “I guess we’re even then.” He scratched his long beard. “July 3rd. Was that a Friday?”

”It was.” Pops stared down the street. “A Friday that changed my life.”

Bluecoat said, “Friday, July 3rd. Same day I lost mine. If I remember—”

Pops interrupted, “I was crawling away from the stone wall when they captured me and sent me to one of y’all’s prison camps near Elmira, New York. That’s where I cooled my heels—or rather heel—for the rest of the dang war.”

“Like I said, we’re even.”

Pops’ face reddened. “I lost a lot more than a laig up there.”

“I’m sure you did.”

Pops placed his right foot beside the Yankee’s left one. “What size do you wear?”

“9-E.”

“Me, too.”

Bluecoat extended his hand. “My name’s Plott. Hiram Plott from Illinois. Just arrived down here with my wife and four daughters.”

Pops studied the open hand. “I don’t shake hands with the enemy.”

Bluecoat shrugged. “No hard feelings. It’s over on my end.”

Pops turned away. “It won’t ever be over on mine.”

That exchange should have ended any chance for friendship between the two one-legged Civil War veterans. But my father said in the coming weeks, Pops would faithfully stop by and harass Hiram Plott at the Yankee’s makeshift whiskey barrel office from where he watched the river traffic while buying and selling cotton.

My father remembered Christmas Eve of ‘82 as unusually cold for Louisiana. Hard times led to low expectations for presents. He never knew how his mother—my grandmother—did it. She scraped up enough money to buy a Christmas present for Pops: a brand new pair of riding boots to replace the patched and resoled one he’d been wearing since the war.

When Pops opened the box and saw the boots, he began crying, realizing the personal sacrifice that was behind this gift. Slipping the left boot on, he said, “Fits perfect.” Glancing down at the spare right boot, he tapped his wooden leg. “I‘ll keep that one in case my hickory stump sprouts a foot.”

What happened next is why this story is memorable. My grandfather called to my daddy, “Son, let’s go downtown.” Pops, carrying a tote sack over his shoulder, kept looking down at his new boot. “I can’t believe Elsie got me a new boot.”

In spite of the cold, Hiram Plott was at his usual spot, drinking coffee and staring across the checkerboard and the empty chair in front of it.

Pops unshouldered his sack. “Got something for you, Bluecoat.”

Plott glanced up as he moved a red checker. “Crown me.”

My grandfather pulled the new leather boot out of the sack, tossing it against the barrel and scattering the checkers. “See’uns, I can’t use the right one, thought you might could.”

Plott picked up the boot. “9-E, huh?”

“Yep.”

He slipped off his own muddy boot and replaced it with the new one. “Fits perfect. That’s right nice of you.”

Pops nodded at his own matching boot. “Christmas gift.”

Hiram Plott extended his hand. “I appreciate it.”

Pops didn’t hesitate in grasping the outstretched hand. “You’re welcome.”

Plott motioned to the empty chair. “Let me buy you a cup of coffee, Reb.”

Pops hobbled over. “You like checkers?”

“Like the air I breathe.”

Pops moved a black checker. “Loser pays for the next cup of coffee.”

On that Christmas Eve in 1882, the two veterans began their weekly Friday checker match that continued until the first one died in 1921. They never called each other by their given names; it was always “Bluecoat” and “Reb.”

They shared boots for the remainder of their lives, but that’s not all they shared. Eventually, they shared grandchildren. Hiram Plott’s oldest daughter eventually met my father, and as you can guess, Bluecoat’s daughter and Reb’s son fell in love.

They are my mother and father.

The two checker players were my two grandpas—Abram Terry and Hiram Plott.

To me, they were Pops and Gramps.

I’m their oldest grandchild, born three years after that first checker game.

I sat with them on many future checker Fridays and learned a great deal. They taught me much more than defending against double jumps and protecting your corner. I learned the valuable truth that two men with opposite views and backgrounds can find friendship if they have at least one thing in common.

In this case, a boot for the left and a boot for the right.

My Grandpas’ boots.

Although My Grandpas’ Boots is fictional, Hiram Plott was my mother’s great-grandfather. My wife DeDe is a descendant of “Abram” B. Terry.

In honor of these two family lines and my favorite two women, here is each of their most famous recipes.

Mary Plott Iles

Dry Creek Pecan Pie

“I was given a cookbook when Clayton and I married nearly sixty years ago. I’ve been baking pecan pies by this recipe for that long.”

½ c sugar

¼ c butter or margarine

1 c light corn syrup

¼ t salt

3 eggs

1 c pecans

1 recipe Plain pastry

Cream sugar and butter. Add syrup and salt. Beat well.

Beat in eggs, one at a time.

Add pecans. Pour into 9-inch pastry–lined pie pan. Bake in a moderate oven (350°) 1 hour and 10 minutes or until a knife comes out clean.

December 3

CHAPTER 3

Stolen Christmas Trees

“I know I tagged a tree in this area.” My neighbor Mitzi Foreman walks through our Christmas tree farm on a blustery December day.

Saw in hand, I desperately scan the area closest to the highway. “Maybe your tag blew off.”

“No, I tied it securely. You don’t think someone took it?”

I cringe. All of the other nearby good-sized trees are taken and I want my neighbors to have the best tree possible. However, we’re prepared for a situation like this—extra trees are tagged in a remote area of our farm. I walk Mitzi over to a beautiful Leyland cypress in the southeast corner of our field, away from the highway. She loves it and I quickly cut it before she can change her mind.

Later that afternoon, Daddy and I look for the missing tree. He points to a jagged stump. “Someone cut that tree with an ax or machete.”

He shrugs. “Someone stole the Foreman tree.”

Who in the world would steal a Christmas tree? I just can’t quite picture a family sitting there on Christmas morning, opening presents, singing “Silent Night” around a stolen tree.

That’s sorry. As my uncle would say, “That’s lower than a snake’s belly in a gulley.”

People will steal just about anything. In the gift shop at Dry Creek Camp, there is an ongoing minor problem with shoplifting. Ironically, the most stolen items are the W.W.J. D. bracelets.

W.W.J.D. stands for “What Would Jesus Do?”

Well, I know this much—Jesus wouldn’t tell you to steal a bracelet—or for that matter, a Christmas tree.

# # #

A few days later, I take my boots off at our front door. Hanging from the Christmas wreath is a scribbled note, “I cut a tree today.” Attached to the note, held by a clothespin, is a twenty-dollar bill.

I kneel and lift our doormat. Under it is another price tag, twenty dollars, and a scribbled note. “Wishing you a very a Merry Christmas.”

My daddy, the world’s most trusting soul, nails up a handwritten sign each year at our Christmas Tree farm:

“If we aren’t home, you can still get your tree. The saw is on the front porch. You can leave your tag, your name, and money by the front door. Now go do your thing.”

I especially love his benediction. “Now go do your thing.”

Unbelievably, this system has worked well. We’ve found that when you put trust in people, they usually come through in an honest way.

The week after the stolen Foreman tree, we notice another stump. The thieves have evidently returned, or someone else has sunk to their low level. I try to remember how many circles of hell there are. Christmas tree thieves deserve to be down there with Hitler, Nero, and the other dregs of history.

I tell my three teenage sons, “We’re going to catch the thieves when they return.”

The next night about 10:30, my middle son Clint and I see the headlights of two vehicles leaving our driveway. We spring into action, running to my truck and taking off in hot pursuit.

We are dressed for battle—I’m in my pajamas and Clint in his boxers and a T-shirt. We catch the escaping thieves within a mile at the Dry Creek intersection.

It’s our moment of truth. I tell Clint, “We’ve got ‘em red-handed now.”

There the culprits are—my mother in her van. Daddy in his truck. They’d left one of their vehicles at the Christmas tree farm going to a basketball game. The headlights we saw were when they returned for the extra vehicle.

Clint and I both burst out laughing. I feel like Barney Fife on one of his overreactions in Mayberry.

My wife DeDe is waiting at the door when the heroes arrive back home. After we sheepishly tell our story, she asks, “Well, what would you boys have done if you’d caught up with the real thieves?”

I look at my nightclothes and shrug. “I guess I’d have taken off one of my house shoes and beat them with it.”

# # #

In the coming week, I try to balance the frustration of a tree thief against dozens of honest families and friends coming to select a tree.

A neighbor arriving with a jar of coins to pay for their tree.

The excitement of warmly dressed preschoolers running through the trees laughing and singing is enough to put anyone in the Christmas spirit.

The fun of letting a five-year-old boy hold the other end of the saw as he “helps” me cut down a tree. As the tree falls he loudly shouts, “Timmbbbeeer.” He’ll always remember “cutting down that tree” during a Christmas season so many years ago.

A tree is special to a young child as this story illustrates.

A local preschool class came for a classroom tree. They paraded off the bus running to the four winds.

Several parents came to help their child select a tree for home. Four of five trees were cut before the preschoolers loaded back on the bus. I put the trees in the back of my truck and followed the bus to school. About half way down my driveway, the bus stopped abruptly. Teacher Dianne Brown exited the bus. “Curt, one of the little boys is crying and shouting, ‘I want my tree. That man’s taking my tree. I want my tree right now!’”

It took careful explanation to convince him we were bringing his tree to school.

He thought I was stealing his tree!

# # #

A stolen Christmas tree could make one cynical, but the joyful faces of children drown out any disappointment. Besides, a thief has to live with himself. That’s pretty apt punishment in my book. He or she saved twenty-five dollars but gave up a little of his soul.

The occasional person who takes advantage of us is greatly outnumbered by the folks who are as honest as the day is long. Our honor system works well because of this: most people are good down in their hearts.

In life, we must choose a worldview: whether people are rascals or basically honest. There are plenty of examples at each end of this spectrum.

I recall other examples of “trustful hearts” in our community: Don Gray’s turnip green patch with a crudely lettered sign inviting people to pick all of the greens they need and leave their money in the mailbox.

Farmer’s Dairy and their butter dish bank for people to pay for their gallon of fresh thick milk. This honor system has been in use for years and Mr. Matt Farmer told me it has worked well.

It’s true—in life, we find exactly what we’re looking for. Our attitude and outlook determine how we perceive the world around us.

We can see every person as a potential Christmas tree thief, or we can see him or her as the person who’ll honestly cut his or her own tree and leave the money under the doormat.

It’s a choice, and the choice is ours to make.

We can either say “Bah humbug” or “Merry Christmas.”

I like the sound of the latter much better.

Matt and Dee Farmer live in the Dry Creek house they built together over sixty years ago. They operated their family dairy with sons Ken, Don, and Wesley.

Sugar Cookies

Dee Farmer

4 1/2 c flour

3 t baking powder

1/2 t salt

1 c butter

2 c sugar

4 eggs

1 t vanilla

Sift flour, baking powder, and salt. Cream butter and sugar. Add eggs and vanilla. Spoon out onto pan then press with flour-dipped glass.

DECEMBER 4

CHAPTER 4

Santa Claus is Coming . . . to School

I’ve learned this: life is always better than fiction. You cannot make up a story that outdoes the truth.

Gordon Copeland sat in my office as I read his resume.

“Mr. Copeland, you have impressive credentials for a substitute teacher.”

He was a barrel-chested man in his late sixties. A thick head of white hair and long beard to match it. A hearty laugh. Red cheeks.

“Has anyone ever told you you look like Santa Claus?”

He laughed. “Everyday. In Florida, I did a good bit of Santa Claus roles. Even did a commercial for Coca-Cola. This year I’d like to make a little extra substituting.”

“Good. We always need substitutes for the three weeks between Thanksgiving and Christmas. I’ll be calling you.”

I’ll never forget the first day he worked in the first and second grade hall. It was early December—always an interesting time in our K-12 rural school.

Like electricity, it spread through the hall: Santa Claus is taking Mrs. King’s place today.

He wasn’t dressed in red and white. He had on cowboy boots and blue slacks. But he was still Santa Claus to these first graders.

My job as assistant principal was coordinating the substitutes. I peeked into his classroom several times that day. The students were quiet as a mouse, working at their desks. This was not normal behavior when a substitute teacher was present.

But this wasn’t just any substitute. This was Santa Claus.

He had a weapon stronger than any paddle or time-out corner.

They didn’t want a bag of switches come Christmas morning.

I mean this is a man about whom children sing:

He’s making a list.

Checking it twice.

Gonna find out who’s naughty and nice.

Mr. Copeland’s noontime appearance in the lunchroom created a minor riot. When I set my plate down at the teacher table, one of them commented dryly, “I don’t believe having Santa Claus substitute is such a good idea.”

I nodded. “It’s made Brandon and Willie behave in Mrs. King’s Class.”

“That’s a miracle. But it’s made the other hundred students crazy.”

Mr. Copeland became a frequent sub during that Christmas season. The reaction was always the same. His class was on their best behavior, but the other students couldn’t concentrate with Santa Claus next door or down the hallway.

Gordon Copeland also substituted in the upper grades. They weren’t true believers and didn’t respond with quite the same level of respect or awe.

He became my friend during that year and served our school well.

He didn’t return the next Christmas season. He told me he’d take his chances at department stores and malls “ho ho ho-ing” over corralling students in a classroom.

The next year Gordon Copeland died of a sudden heart attack. I still miss him and smile when I recall him roaming the East Beauregard Elementary hallway to cries of “Santa Claus is here. Santa Claus is coming to school.”

Merry Christmas, Mr. Copeland.

# # #

He knows when you’ve been sleeping.

He knows when you’re awake.

He knows when you’ve been bad or good

So be good for goodness’ sake.

Postscript

I found a wonderful story about the all-seeing eye while reading a biography of the great African statesman, Albert Schweitzer:

Schweitzer related the story of a one-eyed European lumberman who worked near his compound. The lumberman needed to go away on business, so he took out his glass eye, laid it on his desk, and called in his African workers. “I’ll be gone for a while, but I’m leaving my eye to watch your work while I’m gone.”

He returned in several weeks and was delighted that every chore and job had been completed. He had solved the problem of absentee supervision of his work crew.

A few months later he needed to make another longer trip. He repeated his earlier statement and left the glass eye on his desk “to watch things.”

He returned to find work piled up everywhere. Nothing had been done. Dismayed, he rushed into his office to see what had happened.

In the middle of his desk was a large hat. He lifted it to find the glass eye.

As they say, “Out of sight. Out of mind.”

Now what does a glass eye, Santa Claus as a substitute, and Christmas have to do each other?

We laugh at the Africans and their belief in the magical all-seeing eye.

However, there is a true all-seeing eye. It’s called God.

We believe he is everywhere so he sees all. Omnipresent.

Knows all. Omniscient.

He is all powerful. Omnipotent.

Yet, we puny humans think we can put a hat over God and go our merry way. That’s way more silly than believing in the power of a glass eye.

Throughout the Bible we find the term, “Fear the Lord.” There’s lots of discussion on whether this means awesome respect, cowering fear, or more.

The answer is yes.

We should have an awesome respect for God. He created all there is. He controls all things. His ways are far above our ways.

And we should have a healthy dose of fear. Not cowering fear, but reverent fear. A fear factor that affects everything we do—or don’t do. Our actions and attitudes should be seen through the prism of “we will answer before God for ‘every idle word’ one day.”

My personal take on this is that my fear of God is rooted in not wanting to disappoint Him. I love Him. I revere Him. Yes, I fear him. I don’t want to be found wanting in my commitment and devotion to Him.

Christmas is always a good time for introspection.

Looking inside ourselves at what our priorities really are.

A look in the mirror at whom we’re becoming.

Somebody is watching you and me.

He doesn’t wear a red suit or carry switches.

Neither does he have a glass eye.

Somebody is watching me.

If I truly believe that, it’ll make a difference in how I live.

DECEMBER 5

Chapter 5

What it Means to Believe

This excerpt from my recent novel, A Spent Bullet, is a conversation between Harry Miller, a young soldier, and Levon Reed, the father of the girl he plans to marry. It’s a conversation between two men about belief.

A ninety-two-year-old cousin of mine wrote, “I’ve taken college religion classes and lived nearly a century. Mr. Reed’s A Spent Bullet explanation of belief and being born again may be the best I’ve ever heard.”

Sit back and eavesdrop in on this 1941 conversation in a Louisiana pasture.

Levon Reed spat again. “Boy, you might fit in with this family after all.” He tossed a loose end of wire at Harry. “Now start making yourself useful.”

The only sound was Levon Reed’s tuneless whistling. As the last of the wire was rolled up, he stopped. “Harry, I know we seem like backwards folk to a city boy like you, but we’re just different.”

He pointed toward a nearby lone pine. “Our tap root’s pretty deep too.”

“Mr. Reed, your tap root is way deeper than mine will ever be.” Harry picked up a coil of wire. “I got a question that’s been bugging me: What do folks mean when you talk about being ‘born again’?”

Levon Reed hefted three rolls of wire on his shoulder. “It’s something that happens in a fellow’s heart.” He seemed deep in thought as they walked toward the house.

“Let me give you an example: My boy, Jimmy Earl, joined the Air Corps. He and I both love aeroplanes, but there’s a distinct difference. He’s flying in them now. I’ve never flown in one and probably will die without getting off the ground.

“We both believe planes can fly, but there’s a difference in our beliefs. Jimmy Earl believes in planes. He’s willing to put his butt in a seat and let someone fly him up into the wild blue yonder. Me? I just believe about planes. I believe they can fly, but I’m not willing to commit.”

Mr. Reed pointed to his head and then his heart. “There’s a heap of difference between head knowledge and heart knowledge. It’s commitment. A willingness to strap yourself in and trust something else or someone. I believe a fellow’s ‘born again’ when he goes from standing on the ground admiring the plane to crawling in and trusting. It’s letting Jesus be the pilot of your life.”

“Do you trust Jesus like that?” Harry asked.

“Sure I do.”

“Even . . . uh, even after what happened to Ben?” Harry shuddered at his own question.

Tears filled Mr. Reed’s eyes and he sighed. “That’s a good question and also a hard one.” He removed his hat, wiping his forehead. “I’ve been trusting Jesus all of my life. I’ve trusted him with all I’ve got, including my family. I can’t get my arms around why God let Ben die—been talking to the Lord about it—haven’t got a good answer yet.”

“Do you think God caused the accident?” Harry said.

“Heck, no. A boy chasing a dog ran out in front of a moving truck. That’s what caused it. I don’t believe God caused it, but I do believe he allowed it. And I trust him in spite of my son dying.”

“How do I get that kind of faith?”

“I believe you’re getting it.”

“But I haven’t . . . I haven’t felt any fireworks go off.”

“Fireworks ain’t a sign of being born again. I’ve seen folks jump high for Jesus and two weeks later be back living like the devil. My experience has been that being born again happens in an instant, but becoming a true follower of Jesus—growing to be like him—is a lifetime process.”

Harry kicked at a clod of dirt. “I can feel some changes, but there’s a lot more needed.”

“It’s a process. It doesn’t happen overnight. Let me see . . . .” Pulling his pliers out, Mr. Reed clipped off the wire. “Son, let me think about how to best describe this growth process.”

The old farmer walked in silence for the next minute. “I was in the Great War. When my unit went across the Atlantic—The Big Pond—I studied that big ocean liner, and watched how they adjusted course. It wasn’t all at once. It was more a matter of the captain bumping—or nudging—that rudder a wee bit at a time. Crossing the ocean on a liner isn’t made with 180-degree turns, but steady bumps on the wheel. Same thing’s true in life-change. Often it’s a series of gradual changes that determine a man’s course and direction.”

“…He then brought them out and asked, “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?”

They replied, “Believe in the Lord Jesus, and you will be saved. . . .”

Acts 16:30–31

Chapter 6-10 will be posted early on the morning of December 6.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller