DWW Driving While White

Like all Americans, I’ve been stunned and confused by events of the past few months. Our country is hurting and is extremely divided. It’s easy to deny and ignore it, but that doesn’t make it not so.

As part of a national discussion, we need to sit down and listen to each other. It is a great opportunity for me, as a white man, to sit down and listen to my black friends.

Just listen. Ask questions. And listen. And pray.

I want to do the same thing with my many friends in law enforcement. They and their families are also hurting.

It’s time to listen. Ask questions. And listen. And pray.

In some ways, I have a unique perspective. I’ve just spent three years as a minority in Africa. Whites are pretty scarce once you get out of the cities in Uganda, South Sudan, and Chad. I quickly learned that one of the prices of living in Africa is being guilty of driving while white. We called it DWW.

In no way am I making light of what happened recently in Minnesota, Dallas, Baton Rouge, or Charlotte.

The first time I was pulled over for Driving While White was soon after we’d arrived in Uganda. Traffic police wear white uniforms and stand on the left shoulder (Uganda drives on the UK side of the road). If the officer wants you to pull to the shoulder, he gives a hand signal.

It is often difficult to know if he (or she) is pulling you over or an adjacent vehicle. During my first weeks in country, my hands would be sweaty just seeing the silhouette of the officer.

DeDe and I were traversing the busy road that connects Uganda’s capital, Kampala, to our home in Entebbe near the International Airport. We passed a policeman and I was unsure if he motioned me to the side or not. Looking in my rear view mirror, I saw no reaction from the man, so I continued on.

Within a few kilometers, a police truck with six armed soldiers riding in the bed pulled us over. A policeman leapt out and got in our truck. He began lecturing me about passing up a traffic stop. He threatened to take me back to headquarters where they would impound my vehicle.

Unless I paid him 200,000 shillings.

That’s about $ 80 USD.

DeDe and I had a long trip planned the next day to the border. The thought of losing our vehicle even for a few days worried me deeply.

I asked the officer to allow DeDe and I to talk. He exited and stood, arms folded, talking with the armed soldiers. It was intimidating.

DeDe and I discussed our options.

We made the decision to pay the bribe. Yes, it was a bribe.

It was my first and last time to pay a cash bribe to a policeman or soldier.

But it wasn’t the last time I was stopped for DWW.

If we were out on the road, it was a daily occurrence.

I came to understand that when policeman saw my white face, many times they were going to pull me over. It was a good chance to get money from me.

For the first month or so, I had a knot in the pit of my stomach each time we approached a traffic policeman.

Then I realized it was a game.

And I learned how to play it.

Some of it I figured out on my own.

Most of it, I learned from my co-workers who’d been playing the game much longer.

The first thing I learned was to stay calm.

A white person will never win an argument with an African.

So I made a vow to never be sarcastic or smart.

I made a decision to be compliant.

It’s a word I’ve heard a lot recently in our national conversation.

I had one thing in my favor: my age.

In Africa, I am an Mzee. An elder.

That garners respect, especially if you stay calm.

I learned to ask for mercy/forgiveness/permission “as your father.”

It nearly always worked.

Our record was six traffic stops in one day.

Part of the reason was our mud-covered vehicle. Being a Louisiana redneck, I was proud of being mudded, but learned quickly to keep the lights and blinkers cleaned. That could mean a stop and maybe a ticket.

To deal with DWW, we developed several strategies.

One was to remove the key from the ignition. This was especially important in South Sudan, which is a 21st century version of the Wild West. If a policeman grabbed your keys, you were at his mercy. I usually tucked my key under the seat or on the floorboard.

We made copies of all of our papers, permits, and licenses. This included a copy of our passport photo page and driving permits. I proudly had driving permits for Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan, and Chad, plus an International Drivers License.

I would show the policeman a thick stapled sheaf of these permits.

Never would I hand over my original passport or plastic permits. Once again, if the officer got one of those in hand, you were at his mercy.

African policeman have a whole bag of tricks in asking for a bribe. These strategies range from the open threat (like on my initial stop) to the subtle, “We’d like some tea” or “What do you have for the gate?”

We refused to give cash unless they had paperwork and would give us a receipt. Most of the time, they would allow us to pass. They didn’t want a paper trail on their tea money.

One day in South Sudan, we were at a troublesome roadblock. The policeman was determined to milk us. I finally got out of the car, pulled out my receipt book and started writing a receipt to him. “What is your name, Sir?”

He quickly sent us on our way. He wanted money but no record of it.

Most of the time, we happily paid a bribe request with a bottle of cold water, a piece of DeDe’s banana bread, or even a Bible. I loved to watch the reaction of the officer to our payment. The look varied from great disappointment to a weary smile that we’d played the game well.

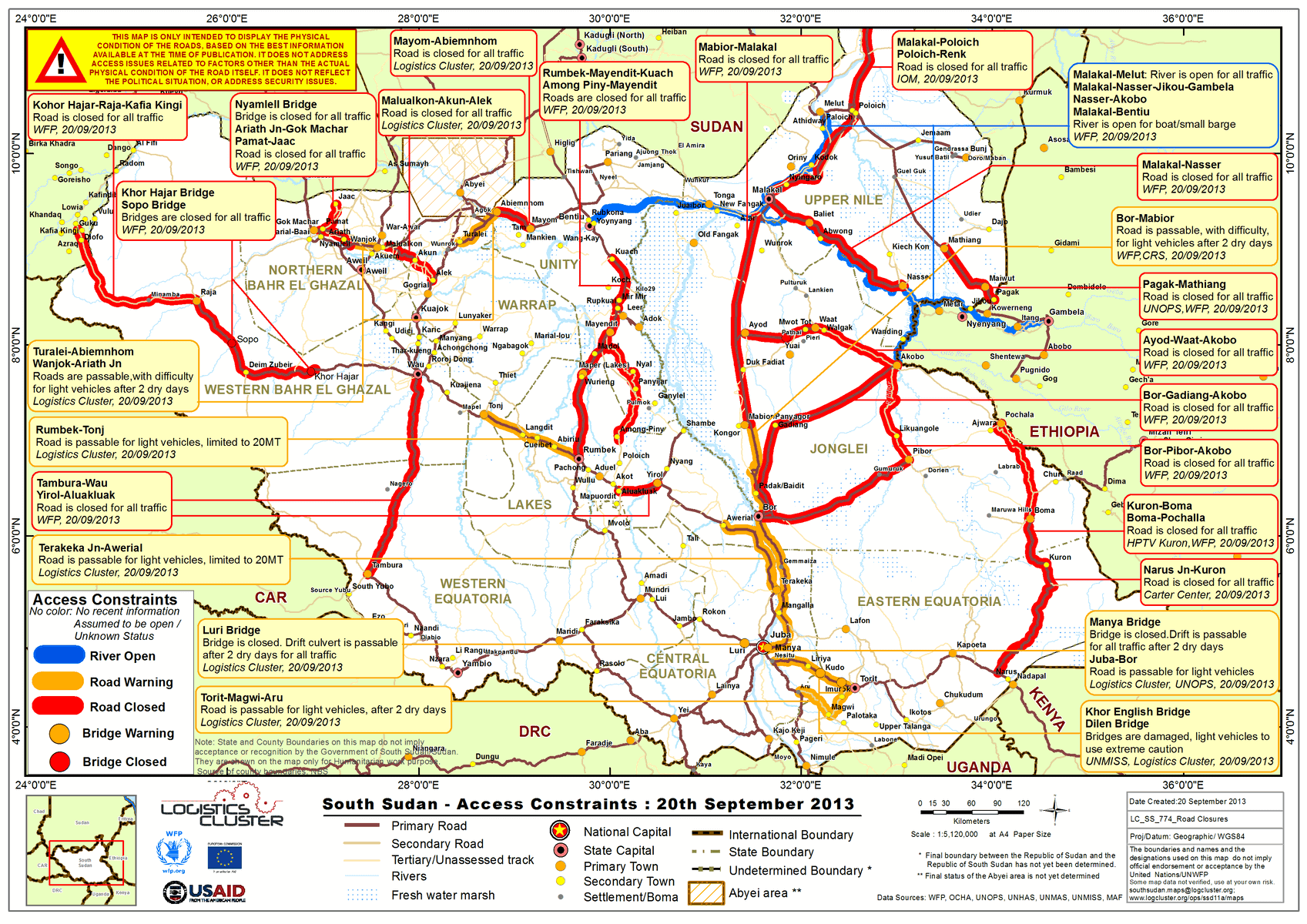

Knowing road conditions in South Sudan is an essential part of planning and research. Roads can be closed due to rainy conditions or insecurity.

South Sudan, with its confused history had confusing laws. It was against the law (according to officers) to drive with sunglasses or in flip flops. Go figure.

In South Sudanese roundabouts, you must turn on your flashers as you enter the circle. I still do this on the Alexandria Traffic Circle.

Many times humility was all you needed at a traffic stop. “Sir, is there any forgiveness in Uganda” usually worked.

One thing that always taxed my patience was the infamous self-fining ticket.

“You were driving on the shoulder of the road. You must fine yourself.”

It was hard to keep a straight face on that one. Many times this meant the policeman didn’t read or write. I never completed my own ticket but wondered what the reaction would’ve been if I’d fined myself a dollar.

There were other schemes that I could only tip my hat to their creativity:

The famous fire tax in South Sudan. They checked to see if you had a working fire extinguisher, then had you pay a fee for certifying that you were carrying one.

The bad road toll fee. South Sudan only has a few hundred miles of pavement. Everything else is rough. There’d be a road block where the policeman would ask for “a donation” for the community keeping their section of road in good repair. This road tax might be repeated five times in a day’s drive.

Once again, we used the rule. If you give us a receipt, we will pay.

My favorite road story took place in northern Uganda. Four of us Americans were driving two Land Cruisers loaded to the brim with luggage and boxes. The Lanes and Jeremiadoss men were moving their families into a remote part of South Sudan. It was a week long trip I will never forget.

Not far from the border, two Ugandan police pulled us over. One was a woman. I feared female policemen much more than the men.

The woman peered into our vehicle, sadly shaking her head. “I must fine you.”

“For what, Madam?”

“Misuse of vehicle.”

“What?”

“You have the passenger seats filled with luggage. That is misuse. The seating area is only for people.”

I glanced ahead at Robert, who was driving the lead vehicle. His body language as he stood outside his vehicle assured me he was getting the same ticket.

It took all of our persuasive skills to get on the road again, with no ‘misuse of vehicle ticket.

One of the joys of my last year in Africa was mentoring a wonderful young missionary named JD Hull. By the time JD joined our team, I was a veteran at police stops and kind of perversely looked forward to them. I viewed it as a challenge or athletic contest.

We were driving along a new road in Uganda. It was straight, flat, and wide enough to land a big plane. (The Chinese build roads with big shoulders) and JD was driving pretty fast.

An officer flagged us down. He had a radar gun, something we seldom saw in Africa. I thought JD was going to cry as the officer showed him the radar reading. The officer smiled. “Mzungu, you are going a little fast.”

JD gripped the wheel. Speechless.

I leaned toward the officer. “Sir, this young man is new in your country. He was speeding but I, as his spiritual father, am asking forgiveness.”

The officer studied both of us.

I continued. “And I, as your spiritual father also, am asking you to forgive us today. I will stand good for him. He’ll drive slower.”

The officer good-naturedly said, “Mzee, I cannot tell you no. You go with my blessing and make sure young Mzungu drives slower.”

I thought JD was going to get out, hug the man, and kiss him on the lips.

DeDe and I laughed with (and at) him for the next hundred miles.

Which by the way, were driven much slower on Chinese Runway 4S heading to the border at Nimule, South Sudan.

I started this story as a foundation for addressing the chasm we Americans are facing over race relations and law enforcement.

The fact that one of the recent tragedies occurred in Louisiana, the state I proudly call home, has troubled me.

My African DWW experiences gave me empathy for what black men and women face in America. Being pulled over, stopped, or confronted for simply looking different.

They call it Driving While Black.

After Africa, I understand a little more.

Like in America, most policeman in Uganda are honest and helpful. One friend, after hearing me complain about DWW, wisely said, “Just remember that the policeman who stopped you probably has a large family and may not have been paid in two months.”

I tried to remember that as I interacted with an official or officer.

I still refused to pay the cash bribe, but understood more.

And understanding is never a bad thing.

It’s called empathy.

And right now the country that I love could use a big dose of it.

Empathy.

Putting myself in the other man’s shoes.

For a day.

For a mile.

For a moment.

Your comments and feedback are welcome, even if you don’t agree. Use form below.

Contact Us!

We love to hear from readers at CreekBank Stories!

For Snail Mail, mail to:Creekbank Stories

PO Box 6060

Alexandria, LA 71307

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller