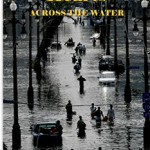

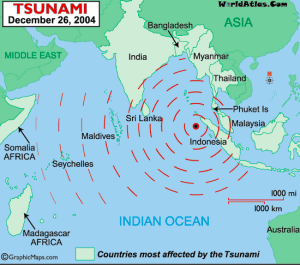

As the tenth anniversary of the Louisiana hurricanes approaches, we’re sharing stories from our book, Hearts across the Water. This week’s posts concern the aftermath of the Indonesian tsunami. I was part of a team that worked there in March 2005.

Beginning next week, we’ll share stories from Katrina and Rita.

Read a sample chapter of the new ebook version of Hearts across the Water.

Chapter 10 : Listening . . . Lost

“There is a way of listening that surpasses all compliments.”

– Van Ligne

Dr. Tim Nicholls is a gifted internist at Willis Knighton Hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Dr. Todd Pullin practices as a pediatrician in Eunice, Louisiana.

These two men were the true leaders of our medical team to Sumatra. Over and over for two weeks we watched them showing the compassion of Jesus to the hurting people of the coastal areas affected by the tsunami.

The American Heritage Dictionary aptly defines compassion as “deep awareness of the suffering of another coupled with the wish to relieve it.”

This is what these doctors did as they sat hour after hour seeing long snaking lines of patients.

After we had been there for about a week, one of the doctors made a statement that will stay with me for the rest of my life: “I thought I was coming over here to take care of the medical needs of these wonderful people. In reality, my being a doctor is only the common ground where I can sit down and listen to their stories. They do not need my medical training as much as they need my ear.”

It was a defining statement for all of us.

For me it was a watershed experience teaching that the greatest gift we can give others is to listen.

The first Westerners to arrive in post-tsunami Sumatra discovered that.

At the Aid House they related a story about eight Tennessee men who came in the early weeks after the tsunami.

Each day they did one thing and one thing only.

They recovered and helped bury the dead.

This thankless task brought incredulous questions from the Indonesians, “Why have you come to do this? We thought Americans hated us and here you are helping do the toughest job of all: burying our dead.”

The grieving Indonesians would stop the recovery team to tell their own story of loss, grief, and survival.

Everyone had a story and, amazingly, wanted to share it with these strangers.

Over and over as American relief workers arrived, they found that these people wanted someone to listen.

All of them, including our team, heard these comments,

“Please go home and tell other Americans about us and what we have lost.”

“Promise that you will not forget us when you go home.”

“Do you have time to hear my story?”

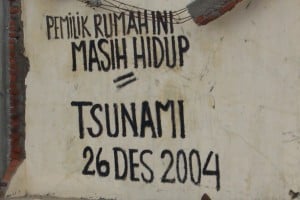

As the people of Aceh province told their stories, a word continually was used by all:

“Lost.”

It was a haunting word when used this way, “We were all together as the wave hit and then they were . . . lost.”

It’s a word without closure.

The vast majority of the thousands of bodies recovered were never identified and simply buried in mass graves. Others were washed out to sea never to be recovered.

Even eighty days after the tsunami, bodies were still being found.

All over the city of Banda Aceh were sticks with red or white cloths tied to them. This meant a body had been found in the rubble at that spot.

Very few of the survivors were able to bury the bodies of their loved ones.

So they used that word. Lost.

Many times they would nod toward the Indian Ocean as they said this. “They are gone. They are lost.”

And our job was to listen . . . over and over . . . as long as it took.

Another person from the Aid house told of an earlier team was the heart-wrenching story of two American nurses who were tending to an Achenese mother.

She told them of how her two babies were washed out of her arms during the tsunami.

Her husband dove in after them. “All three of them are gone… lost,” she quietly shared.

The mother continued, “I’m dry from crying. I have no tears left inside of me.”

So the two nurses sat silently and cried for her.

Just sitting there for a long time and showing that God-like word: compassion.

In one Banda Aceh clinic we met a grandmother with her three preteen grandchildren.

She shared her story:

On the morning of the tsunami she went walking with these grandchildren.

Her daughter, with two younger children, stayed home.

While they were gone walking in a nearby neighborhood, the tsunami struck.

Once again we heard the term, this time from a grieving grandmother.

She shook her head, as she said, “When we returned they were gone . . . gone forever.”

The grandmother’s eyes had such an unusual mixture of pain and dignity.

Listening . . . It is an art and it is a habit.

Sadly, it’s often not conducive to our American way of life.

Another member of our team, Jesse Koski, was the team optometrist. Jesse is a renal nurse in Lafayette but on this trip he was the resident eye doctor.

Jesse is a tough-looking guy with a football player’s build and a shaven head.

He loves people and showed it over and over on this trip.

Our team took hundreds of pairs of eyeglasses to distribute.

Many of the tsunami survivors lost their eyeglasses in the water.

Others needed glasses but had never had the opportunity to have them before.

Jesse would open his large locker of glasses and excited Indonesians would go through the process of trying them on for the right fit.

It was fun to watch the process.

Jesse was good at it and it afforded a great opportunity to once again do what we were really there to do: to build relationships through listening.

Jesse’s satisfied customers would walk away with big grins on their faces seeing things they hadn’t seen before.

In one displaced person’s camp we were shutting down our clinic and loading up the medicine lockers, tables, chairs, and equipment we used daily.

I was over by the temporary buildings the government had erected to get the people out of the weather.

A middle-aged Indonesian man came up and grabbed me by the arm. He had on a pair of Jesse’s glasses. He got right up in my face and began talking rapidly in either Basran Indonesian or Achenese.

At first I thought he was mad but quickly realized he was telling me something important. I looked around for an interpreter but no one was near.

Then it hit me: He was telling his story.

I hope you understand it when I say I didn’t understand one single word he was saying; yet I knew exactly what he was saying.

My job was simply to listen as he told his story.

The passionate waving of his arms and gestures told me all about the giant wave. His facial expressions and voice inflection told me of the great loss he had suffered.

I looked at his dark eyes through the lens of glasses that had been sent from Bossier City or Baton Rouge. His eyes told his story even better than his words or gestures.

I’m not sure how long it took him to tell his story. That’s not important. The main thing is that he got to tell his story. It was really the most eloquent of the many stories I was told.

Without a doubt it is the story that has rooted most deeply in my heart.

One of America’s most beloved authors, Erma Bombeck, shared this story about sitting in an airport and trying to enjoy the peace and quiet before flight.

An elderly lady sat next to her and said, “I’ll bet it’s cold in Chicago.”

Bombeck knew the lady was trying to make conversation, but she was not in the mood for small talk.

She replied to the stranger without looking up, “It’s likely.”

But the lady did not take the hint and continued the one-sided conversation with, “I haven’t been to Chicago for nearly three years.”

Bombeck grunted, “Uh-huh.”

Then the woman said, “My husband’s body is on this plane. We’ve been married for 53 years.”

Erma wrote, “I don’t think I’ve ever detested myself more than I did at that moment.

A desperate human being had turned to a stranger.

She needed no advice, money, assistance, or expertise—just someone to listen.

She talked steadily until we boarded the plane.

As I put my things in the overhead compartment, I heard her say to her seat companion, ‘I’ll bet it’s cold in Chicago.’

I prayed, ‘Please God, let the fellow sitting next to her listen.’ ”

Later in the days and weeks after Katrina and Rita, this same ministry of listening was needed.

And right at The City of Hope evacuee shelter in Dry Creek, Louisiana.

Dr. Tim Nicholls and Dr. Todd Pullin did exactly what they had earlier done in Southern Asia.

They sat and listened as they doctored.

Except this time the stories weren’t of a tsunami wave, but a storm surge wave.

This time it was New Orleans instead of Banda Aceh.

And this time, thankfully, there weren’t tens of thousands dead.

But still, regardless of the culture, city, language, or religion, people wanted to tell their story to a listening ear and a caring heart.

Their stories of loss…

Heard by a compassionate and caring heart.

Hearts across the water.

Always listening … always caring.

Get your ebook copy of Hearts across the Water at Amazon‘s Kindle Store.

If you enjoyed today’s story, please share it with your friends. Word of mouth is how our stories and books become connected to new readers. You are an integral part of this.

Post Contact Form

This goes at the bottom of some posts

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller