You can order your softcover copies directly from our website here.

Copies are $15 each plus $5 shipping per order, and you can pay via credit card or Paypal.

Scroll down to read back cover copy and sample chapters.

___________________________________

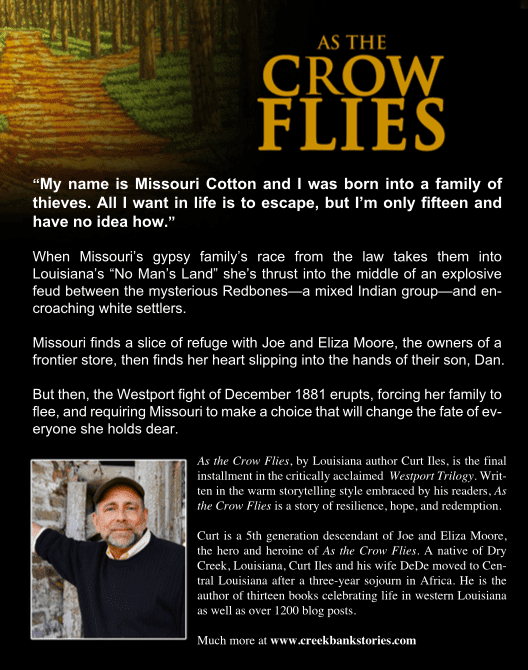

- Every novel has a Story Question. It’s the premise of a good story. As the Crow Flies tries to answer this question: Can a drifting girl named Missouri find home in Louisiana’s No Man’s Land and can she rise above her raising?

Sample Chapters

as of Jan. 16, 2018

As the Crow Flies

by Curt Iles

Copyright 2017 by Creekbank Stories and Curt Iles

Part 1: Drifting

“Just a stranger in a strange land.”

— Leon Russell

We have no power over external things, and the good that ought to be is found only within ourselves.

-Epictetus

CHAPTER 1 — AT THE RIVER

My name is Missouri Cotten, and I was born into a family of thieves. That’s how Pap, Ma, and me found ourselves in Louisiana’s No Man’s Land in early October 1881. Pap, eyeing the riders who’d been trailing us for the past mile, hustled our wagon onto the Calcasieu River ferry. He tossed a wadded dollar bill at the ferryman. “We’re kinda in a hurry.”

The ferryman pocketed the dollar and nodded back up the road. “Your rush have anything to do with those men?”

“That ain’t your worry,” Pap said. “Your fee is two bits, and I’m paying you a dollar to get us across now.”

The man unmoored the barge and began poling us across the river. The three riders, each carrying a long gun, dismounted and walked down to the river. One cupped his hands. “Fellow, you can run, but you can’t hide. We’ll get you sooner or later.”

Ma brushed Pap’s arm. “Henry, you sure they won’t follow us across the river?”

The ferryman, who was stopped and had a gravelly voice, answered her question. “Ma’am, those men won’t cross past here. They’re probably a posse, but their badges don’t mean a thing on the west side of the Calcasieu.” He nodded. “It’s their Dead Line. They won’t cross over into the Outlaw Strip if they can he’p it.”

“Dead Line?” Ma said.

“This here river’s their Dead Line.” He glanced westward across the river. “They don’t go among those people unless they have to.”

“Those people?” Ma said.

“You’re heading into Redbone territory. Best to steer clear of ‘em and keep moving west.” He wiped his hands on his faded bib overalls. “Where you coming from?”

“Alexandria,” Pap said. “We left there due to a, uh, a little misunderstanding.”

The man spat as he glanced behind him. “I can see that. By the way, what’s your name?”

“Whoa now, feller. You taking a census or something?” Pap, who’d been drinking earlier, was already approaching his surly stage, so I eased beside him to diffuse any trouble.

The ferryman raised his hand. “No offense meant. It’s just my job to know who’s crossing the river, in case we need to notify y’all’s next of kin.”

“We’re the . . . ” Pap hesitated. “We’re the, uh, Cotten family.” Pap wasn’t quite yet used to our new alias. “I’m known as Slick Cotten. This here’s my wife, Eula Mae, and our daughter, Missouri.”

I cringed. At this point in my life, I went by Mizz and hated being called by Missouri. That gave Pap all of the more reason for calling me Missouri.

“Is there a difference between No Man’s Land and what you called The Outlaw Strip?” Pap said.

“One and the same,” the Ferryman said. “Sometimes it’s also called the Neutral Strip or simply, The Strip. That harkens back to it being a disputed territory.”

“How far is it to Texas?”

“As the crow flies, ’bout fifty miles to the Texas border at the Sabine River. Normally a four-day trip.” He glanced at our rickety wagon with its mismatched ox and mule team. “It’ll take pert near a week with that buzzard-bait pair pulling you.”

Pap stiffened. “The mule’s name is Maggie and her partner’s Aunt Em. They may not look like much, but they’ve got us here and will git us to Texas. By the way, what’s between here and Texas?”

“Not much ‘cept pine thickets and hog wallows. The part of Louisiana you’re entering ain’t got much civilization, and even less law.” The ferryman grinned at Pap. “I reckon you’ll fit in pretty well there, if they don’t kill you first.”

Pap wiped his brow. “We’ll be safe across the river?”

The Ferryman nodded at the bounty hunters on the receding far riverbank. “You’ll be safe from them.” He glanced westward. “The question is whether you’ll be safe over there.”

The ferry was now in the river’s swift current, struggling to reach the far shore.

From the deck, I kicked a pile of sticks and dried sweet-gum leaves into the muddy river. They swirled together, then suddenly disappeared under the muddy water.

“Why you’d do that?” Ma said. “That might’ve been a patteran.”

“A what?”

“A patteran. A gypsy message.”

“Ma, why are you always looking for this superstitious stuff?”

“Mizz, it’s everywhere if you just slow down and look.”

We bumped against the shore, and Pap hurried our team off the ferry and up the steep-cut bank. The animals strained to get traction and move the wagon out of the loose sand. Still in a hurry, Pap cracked his whip above the team. “Haw, come on, girls, let’s git.” The wagon hesitated, jerked, and then Mag and Aunt Emma pulled us up to level ground.

At the top of the bluff bank, Pap pointed at a red sign nailed to a cypress tree. “Missouri, what’s that say?”

I squinted. “This crossing’s called Hineston Ferry. And the road we’re now on is the Sugartown Road.” A smaller hand-scrawled sign was nailed below it. “That lower sign says, ‘Abandon hope all ye that enter here.’”

“Sounds like our kind of place,” Pap said.

Hope. What a word. I hadn’t had it in a long time and had no illusions that crossing this river would change anything.

The ferryman waved, then lowered his voice and growled. “Good luck. Stay on the road and keep amoving.”

Ma leaned out her side of the buckboard, looking behind us over the canopy.

“Are they still there?” Pap said.

“No siree, as far as I can see, they’re gone.”

Soon we left the hardwood swamp and entered a vast stand of towering capines. Whatever this mysterious new land might hold, it was sure different from the open cotton plantation country of the lower Mississippi River valley. Our wagon passed out of the hardwood bottom under an endless green canopy of towering pines over the narrow road. The pine tops blocked out the sun, casting the forest into cool shade. The only sound was the steady wind up in the pine crowns and our creaking wagon rolling on the thick carpet of pine straw. When we stopped to rest the team, the eerie silence filled me with dread. I understood why this was called No Man’s Land. It seemed a fearful place where humans were unwelcome.

A flock of cawing crows circled our wagon. Ma, using her hand to shield her eyes from the sun, said, “Those crows are a sign.”

Pap’s hackles rose. “Woman, I don’t wanna hear none of that flapdoodle.”

She whispered to me. “Mizz, those crows are a sure sign. We oughta go back.” Several of the birds landed, cawing and hopping about on the red clay road. “That murder of crows . . . is trying to tell us something.”

“Ma, I thought they were called a flock?”

Her eyes widened and she spoke slowly. “No siree Bob, that’s a murder of crows . . . and they’re trying to warn us.”

“Of what?”

“Nothin’ but trouble and death.”

“Where?”

“Somewhere up ahead.” She turned to Pap, an icy fear in her voice. “Henry, please turn back.”

“Too late for that.”

He was right. As much as I hated to admit it, Pap was right. We’d crossed the river, and there was no going back.

One more river. One less chance of us ever putting down roots. One more reminder that we’d never have what I could call a home.

2

In the Pines

Our wagon jostled along the narrow, rutted road, the left rear wheel squealing badly. “That back axle’s not goin’ to take us much farther.”

“I can smell the wheel burning,” Ma said. “I told you to get some axle grease.”

Pap clenched his fist. “Woman . . . shut your mouth.”

“It would not’ve hurt none to’ve asked a passing wagon for a little grease.”

“I don’t wanna hear no more of your sass.”

“But I just—”

“Shut up, or I’ll shut you up.”

Squeezed between them on the buckboard was a dangerous spot when they were sparring, which was most of the time they were awake. As Ma pouted and Pap fumed, we rode in relative silence for the next mile or so. I began humming “In the Pines” hoping that music would soothe the savage beast, or in this case, beasts. Hoping Ma, who had a wonderful alto voice would join me in the song, I finally worked up the courage to sing the words,

“In the Pines,. in the pines, where the sun never shines

Neither of them said a word. It was the wind whipping up high and my singing. I was used to Pap and Ma always being at each other’s throat. If one said, “cat”, the other one said, “dog.” There was never a moment’s peace.

On my seat in the wagon buckboard, I was wedged between two of the most complicated people in all of North America.

Just as we neared a small branch, the wagon jolted to a stop. That wheel had finally frozen up. Pap crawled under the wagon. As soon as he was out of earshot, Ma said, “Your pap’s hard to be around when he gets like this.”

“Then why in the world do you stay with him?” I asked.

“Because he’s my husband . . . and uh, your Pap.”

“You could probably do better.”

“Maybe so. He ain’t the kind of man I wanted, but he’s the kind of man I got.”

“I believe I’d cut his throat one night while he’s sleeping off a drunk.”

“Don’t talk about your Pap like that.”

“Or I’d cut my own throat.”

“Girl, hush that. Besides, I lean on him when I’m crazy, and he leans on me when he’s drunk.”

“What about when you’re both off kilter?”

“We jes’ lean on each other.”

“Well, if that’s what marriage is, I believe I’ll pass.” I felt the old bitterness seeping up. “Anyway, marriage shouldn’t be about him hitting you.”

“Mizz, he only does that when’s he been drinking.”

“That’s no excuse.” I was working up my courage, which wasn’t always a good thing. “His stealing and conning is gonna get us all in jail . . . or worse.”

“He is pretty good at staying ahead of the game. I’ve always said he was so slick he could slide uphill.”

“Is that how he got his nickname?”

“That and his bald head.”

Just then, Pap began cussing and kicking. He crawled out from under the wagon. He’d raised up and cut his head on the axle. Blood was running down his face and he angrily threw a monkey wrench at the wagon.

“Mizz, go get a towel.”

She sat Pap down and went to working on his wound. Ma was from a long line of Indian healers. The Louisiana Cajuns call healers like her traiteurs. Ma’s gifts had been carefully passed down through generations: she could draw fire from a burn, cure poison ivy, or mouth thrush.

Her specialty was staunching bleeding. I never tired of watching it. I’d watched Ma staunch bleeding on a hunting dog that’d been ripped open by a hog. Another time, when we were near Meridian, Mississippi, a neighbor boy cut his leg bad on barbed wire and she used her gift to stop the bleeding.

She always carried a little bag of herbs and pastes. She wadded up some leaves, spit on them, and applied to Pap’s cut. Then she whispered a bunch of Indian talk in Pap’s ear. She claimed it was from the Old Testament. She switched to English and I scooted closer to hear. “And when I passed by thee, and saw thee polluted in thine own blood, I said unto thee . . . Live; yea, Live.”

She kept repeating this as Pap wiggled and cussed, but amazingly the bleeding stopped.

“Is that from the Bible?”

“It’s in Ezekiel.” She closed her herb bag. “Mizz, I need to pass that gift on to you.”

I was curious but wasn’t sure I wanted her gifts. I’d seen them cause nearly as much trouble as Pap’s stealing. She swore these gifts, that she called the touch, came from God. Some folks agreed with this assessment, while others suspiciously viewed her, and her touch, as instruments of the Devil.

“Missouri, go get my bottle,” Pap said.

I acted like I didn’t hear him.

“My bottle. It’s in my boot under the wagon.”

I slowly made my way there, reluctantly handing the whiskey jug to him.

He took a long slug. “Best painkiller there is.”

Ma, under her breath, said, “He puts a thief in his mouth to steal his brains.”

“What’d you say, Woman?”

I stepped in. “She asked if the wagon was fixed.”

He wiped his mouth. “This is as far as we’re going for now.”

“We should’ve turned back,” Ma said.

To escape their coming storm, I slipped off the wagon, grabbed a bucket, and headed to the creek for water. Claws, our wagon cat, hopped down and followed me, meowing.

“Yep, you’re hungry. So am I.”

Rain frogs, sensing a change in the weather, croaked in anticipation.

Across the creek, a distant crow called.

The cat rubbed against my leg.

“Did you hear that, Claws?”

The crow, now closer, called again. A neighboring bird cawed from near our wagon. I shivered, wondering if Ma had heard it, too.

As if in recognition of our predicament, dusk fell and a cold rain began.

3

Two Wagons

That first rainy night in No Man’s Land we made camp beside our broken-down wagon. My folks set up an old army tent in a nearby clearing. I preferred a pallet in the bed of the wagon. It was just me, Claws, and a book. Using a short candle, I hoped to read a few chapters before it went out. The rain intensified and I positioned my bed away from the leaks in the canopy. I patted the double-bit ax beside my pallet in case any varmints showed up, especially the two-legged variety. I read until the candle flickered. I placed my book in a canvas bag and settled down, dozing off to the drumming of rain on the canvas covering.

* * *

I woke to the sound of Ma scraping a pot. I got my Bible out of the book bag and moved the ax aside. I heard sizzling and inhaled the wonderful aroma of frying bacon and fresh coffee. In spite of my depression over being stranded in this God-forsaken wilderness, any day that began with bacon was a good day.

I peeked out from the canopy to see Ma leaned cooking over the campfire. She smiled, “Morning, Mizz. How about a cup of hot coffee?”

I sat on a log beside her. “Don’t you ever get tired of cooking on the ground?”

“It’s about the only way I know. It’s been pert near a year since I last cooked in a kitchen. This is just the way it is.

Pap, with a bandage on his head, came out of the tent and said, “Lookee there.” A Conestoga wagon approached from the west. Pap sat beside me on the log, placing his long tom shotgun between his knees. “Don’t forgit—our name is Cotton.”

A man and teen girl sat on the buckboard of the wagon, framed by four blonde curly-headed girls peering from the canvas opening.

Pap tipped his hat at the wagoneer. “Mornin’. Where are ya’ll headed?”

The man glanced back. “As far from here as possible.” He stopped the wagon and the passel of girls piled out. From behind the canvas, a baby’s raspy cough caught my attention.

One of the girls looked about my age, and I followed her to the back flap of the wagon.

“That baby sounds bad sick,” I said.

“That’s why we’re headed back to Alexandria. Ain’t no doctors out here.”

I peered under the canvas at a sad-eyed woman holding a newborn. The woman wiped her face then looked away.

I climbed onto the wagon bed. “Ma’am, my ma’s a healer . . . she might can help with your baby.”

“I’m afeared he’s beyond help.”

I felt a hand on my shoulder and heard Ma’s calm voice. “I can sure try.”

The mother’s voice was desperate. ”We done buried two other boys in this God-forsaken place, and I’m scared of losing another.” She glanced at the girls who’d crowded around. “I can keep girls alive, but ain’t much good with boys.”

Ma tenderly took the coughing, swaddled baby. “He’s burning up with fever. What’s his name?”

The woman gazed away. “Ain’t named him yet . . . waiting to see if he makes it.”

Ma’s jaw tightened. “I’ll try to help, but you gotta promise me you’ll name this baby. Don’t nobody deserve to live . . . or die . . . without a name.”

The mother was chagrined and nodded at Ma. “What’s your name?”

“Beulah. Beulah Mae Cotton, and this is my daughter, Mizz..” Ma winked at me. “We’re the Cotton family. Mizz, now how do you spell it?”

“It’s C-o-t-t-on,” Because our family name changed from town to town it was a chore keeping her up with spelling our names. During our time in Alexandria, Pap was known as Doug Taylor and Ma was Katherine, his wife.

Ma stepped toward the woman. “How long y’all been in this here country?”

“Going on two years.” The woman nodded out the back of the wagon where her husband and Pap were deep in discussion. “My man wanted homestead land. There’s lots of free land out here, jes’ ain’t much of a life.”

“We ain’t done much better in our wanderin’,” Ma said.

“Where are you all headed?”

“Texas.”

The mother put her hand on Ma’s shoulder. “Lady, you’ll never get your family through this strip alive. Turn around.”

Ma whispered, “Crows,” before shaking herself. “Let’s take a look at that baby.”

The mother handed her the baby. “How you gonna heal him?”

“With the help of the good Lord and that fire over there.”

“Fire?” The mother reached for her baby.

“Please trust me . . . I need you to trust me,” Ma said.

The woman crossed her arms and stepped back.

We climbed out of the wagon and Ma led us to the smoldering campfire. I’d never watched Ma heal with smoke. She knelt, muttered a prayer, pulled some dried herbs and roots from her satchel, and tossed them into the smoking embers. The fire flared up, giving off a thick gray smoke.

Ma unbundled the baby and held him directly above the smoke. He choked and screamed. The sisters’ curious looks deepened to concern. The baby’s father hurried over. “Whatcha doing to my baby?”

The mother waved him back. “Leave her alone. She’s healing him.”

It looked to me like Ma was killing him. In a low voice, she hummed into the howling baby’s ear, still wafting smoke in his face. Finished, she handed the baby to his mother. “All right, Momma. I’ve done my part.”

Ma stepped squarely in front of the mother. “Now it’s your turn. What are you going to name this fine boy?”

The mother gazed at her red-faced sputtering baby. “Cotton. I like that name. We’ll name him Cotton after y’all. All my other kids are cotton-tops. His name will be Cotton Nash.” She winked. “If it’s all right, with two O’s.”

Ma smiled. “Cotton’s a good name for a boy. I predict he’s gonna grow up to be a fine man.”

The baby was still wailing, but the mother smiled wearily. “Thank you kindly.”

Ma patted her shoulder. “You get to a doctor when you reach civilization across that river, but I believe he’s gonna be okay.”

The woman climbed onto the wagon. “Where’d you get your gift?”

“From the Lord.”

“God’s blessed you.”

Ma laughed bitterly. “Not sure if it’s a blessing or a curse.”

The woman reached into her pocket. “I don’t have much, but I’d like to give you something.”

Ma held up her hand. “Nope, I don’t take nothin’ for helping. That ain’t how it works.”

I stole a look at Pap and wasn’t surprised at his scowl.

The Cottontop-Nash family loaded onto their wagon. The baby had the dry heaves but wasn’t coughing as badly.

I eased beside Ma. “You really think he’ll make it?”

She nodded. “Yep, I do.”

The wagon moved slowly away as the entire Nash clan waved.

One word came to mind: lost. They were just as lost as us. Drifting and lost.

Just as their wagon topped the hill, the lady shouted back. “God bless you.”

Pap spat. “God he’ps those who he’p themselves, and we just missed our chance.” He grabbed Ma’s arm. “Those people wanted to give you something—and you turned them down—and us with a broken wagon and empty pockets.”

Ma jerked away. “I’ve never took money for my gift.”

Pap held out a weathered paper. “That fellow on the wagon gave me his homestead deed. Said they weren’t ever coming back and wouldn’t need it.” He handed the paper to me. It was a homestead filing with a bunch of legal terms and descriptions. The man’s legal name was Graham Nash and the deed was for eighty acres in Calcasieu Parish near a place called Sugartown.

I handed Pap the deed, and he put it in his vest pocket. “We’re going to Texas but can check this out if we pass near there.”

“Missouri,” Pap said, “that Nash man mentioned there’s a general store about three miles past here. I’m sending you for supplies.”

“How will I pay?”

He pulled out several wadded bills and a fistful of coins. “Here’s a little, but it’ll be up to you to get the rest.” He winked. “Use your charm.”

I held one of the bills to the light. “Is it real or counterfeit?”

“Does it matter? We need wagon grease, some flour, sugar, coffee, a half pound of eight-penny nails, and tobacco, both the smoking and chewing kind.”

I held out the money. “This isn’t enough.”

He shrugged. “Beg it, steal it, or whatever . . . but bring it back.”

“Can I get a candle?”

“As long as you bring back the other items.”

I wrote the items on a scrap of paper, and then read them back to Pap. I knew from experience about this kind of thing. Walking away, I rubbed my cheek. The bruise was nearly gone from the last time I’d come back empty-handed from an assignment. I was determined that this mission would be successful. I hurried away before he added any items to my shopping list.

Some publishers and readers are offended by inclusion of faith healing, folk remedies, traituers, etc.

What say you?

Do you have any good folk stories about these type of healings?

Post Contact Form

This goes at the bottom of some posts

4

A Stranger in a Strange Land

I’d walked nearly a mile to the store when I came to a creek crossing. A man was sitting on the far bank of the creek, holding a fishing pole. That was something about him that gave me the creeps. I’d learned that girls alone had to be careful around strangers, so I scanned the creek for a better place to cross.

He halloed me, then said, “Use that log ri’t there for crossin’. Don’t worry, it ain’t but knee deep where the log ends.”

“How’s fishing?”

“Caught a perch or two. Mainly checking my set lines. Caught three channel cat overnight.”

I hiked my skirt up, walked the log, then stepped off into the creek. I gritted my teeth. “That’s cold.”

The stranger laughed. “Cherry Winchie’s cold this time of the year.”

“What’s a Cherry Witchie?”

“It’s what you’re wading in, Sister. This is Cherry Winchie Creek.”

He waded toward me. I warily watched him as he neared. He was Indian-looking and kind of dried up like old men often are, as if he’d blow away in a strong gust.

He stood at water’s edge, hand out, wearing a lopsided grin. “Wanna know how it got its name?”

“Sounds as if you’re going to tell me, whether I want to know or not.”

He waved off my comment. “My grandma said it got its name from a Cherokee woman who lived on the creek. You know, Cherry . . . Chero-kee.”

My sense of unease lessened, but I knew not to let my guard down. As he reached for my arm, I instinctively stepped back.

He laughed. “Oh, don’t worry about me. They say I’m just a harmless idjit.”

“What?”

“Idjitt. I’m the village idjitt. You know, touched in the head. My cornbread ain’t all done.” He said this with a smile as we waded together out of the creek. I sat on a stump and put my shoes on. I noticed two things about him: that crooked smile and his piercing, smoky-black eyes that took in everything. For some reason, I sensed him as trustworthy. Besides, he was so old, I could easily outrun him if he started any trouble.

He scanned the ragged clouds. “That north wind is raw. Hog-butchering weather today, ain’t it?”

I didn’t answer.

“Where are you headed, Honey?”

“The store.”

“What’s your name?”

“Mizz . . . uh . . .” My mind went blank. “Mizz Whitehead. I mean Cotton.” I was still struggling with our latest alias. Before we were the Alexandria Taylor family, we’d been the New Orleans Whiteheads. The similarity of the assumed names threw me for a loop.

“Well, Miss-Miss-Uh-White-Cotton, mind if I walk withcha?”

“If you’ll tell me your name.”

“I’m Nathan Dial, but folks around here just call me Unk.” He grinned. “It appears I know my name better than you do your’ns.”

I laughed in spite of myself. “Can you show me the way to the store?”

That was all of the encouragement he needed. “Yep, I can remember my name, all right, but I have trouble keeping up with what day of the week it is. Today’s Thursday, ain’t it?”

I counted on my fingers. “Nope, I believe it’s Friday. The seventh of October.” I tied my last shoe. “How far to the store?”

“As the crow hops, it’s three miles.”

“I thought the saying was ‘as the crow flies’?”

He shrugged. “Don’t matter. It’s pert-near three miles either way. Uphill or downhill.”

“What’s past the store?”

“Nothing much until the village of Sugartown.

“As the crow hops?” I said.

“Yep.”

“Uphill or downhill?”

“W’all. You’re ketchin’ on.” He had a pretty bad speech impediment, but his sense of humor wasn’t impaired.

Pap’s land deed had mentioned Sugartown, so I asked, “Have you been to Sugartown?”

“Nope. My kind ain’t welcome there.”

“Your kind?”

“Yep, my kind. I’m a Redbone. A Ten Miler. Sometimes, we jes’ call ourselves The People.” He placed his arm beside mine. “Child, you and I are about the same skin color.”

“I’ve always been dark. That’s why I wear long sleeves. I’m trying to hide my color.”

“You part Indian?”

“I guess so. My momma’s people are Mulungeons from the Carolina mountains.”

“Never heard of ‘em.”

Ma says our people were Portuguese who were shipwrecked on the Atlantic coast and moved inland to the mountains. There we mixed with the Indians and who knows what else.”

“You been there?”

“No sir. We’ve been on the road for all my life.”

“How long is that?”

“I turn sixteen this month.”

“You seem pretty smart for a girl who don’t know her own name.”

“And you’re pretty nosey for a fellow who’s touched in the head.”

He grinned. “Well, dog my cats, Miss-Mizz. I believe you and I are going to get along real well.” He led me around the mud holes on the narrow road. “Being touched in the head comes in plenty handy. It kept me out of the war, and people speak freely around me because they think I’m stupid. I learn a lot jes’ listening.”

“Mister, you don’t seem stupid to me.”

“You can call me Unk or Mister Unk.” He squinted. “Miss-Mizz, you got a lotta sand being out here alone in No Man’s Land.”

“Sand?”

“Yep, sand—or grit.” He stood in front of me, staring. “Where’d you get those eyes? They ain’t Indian eyes.”

I blushed. “People always notice my eyes. They’re not brown like Pap’s or Ma’s.”

Unk squinted. “They got a little bit of everything in them. Never seen nothin’ like ’em.”

I was used to it. My mixed eye color was like my mixed heritage: it always drew attention, sometimes unwanted and unwarranted.

“We’re nearly there, Miss-Mizz.”

“My name’s Mizz and you don’t have to call me Miss.”

“That’s no problem, Miss-Mizz.”

I had a feeling I’d made a new friend who’d never get my name right.

We climbed a rise and the store sat in a clearing in the pines. As we neared, I read the sign above the porch:

Hatch and Moore Store

General Merchandise.

Westport, La.

“How long has the store been here?”

“About two years…” Suddenly, Unk Dial stepped off the roadway into the pines. I thought he’d stepped on a snake, but his attention was on four men who stood clustered in front of the store. The tallest one held a rifle in the crook of his arm, and they all sported side arms.

“Who are they?”

“Outsiders. They’re timbermen who want our land. That cat-kicker with the rifle is named Musk.” Unk’s hands were shaking. “Iffen you get in his way, there’ll be trouble.”

“Iffen?”

Yes ma’am, stay out of his shadow iffen you don’t want to git shot.”

“How so?”

“A feud’s been brewing ‘tween our people and those fellers. I’m afeared somebody’s gonna get kilt ’fore it’s over. Musk can’t keep his mouth shut, and I figger he’ll be the first one to kill . . . or be kilt.” Unk grabbed my arm. “This place is jes’ a powder keg waitin’ on a spark.”

I jerked away. “I’m going in the store.”

“Please don’t.” There was real fear in his voice, but I was already half way to the store. Unk called after me, “Ask for the Irishman. He’ll he’p you.”

The men stopped talking as I neared but made no effort to move. The tall one squarely faced me. “And who might you be?”

“Just passing through.”

“A girl as pretty as you shouldn’t be out here alone.”

I nodded toward the woods. “Who said I was alone?”

The men didn’t move. Evidently they were the kind of bullies who liked picking on someone smaller and supposedly weaker. Just as I readied myself to plow right through them, a boy’s voice from the doorway said, “Musk, you and your buddies don’t have enough manners to let a lady through?”

I looked up to see a ruddy, sandy-haired teenager a little older than me. “You fellows let that girl into our store. She may have some money burning a hole in her pocket.”

If you only knew.

At the sound of his voice, a black-and-tan hound bounded out from under the porch and limped to the boy. “Now, Lucky, you be nice to our guest.”

The four men shuffled aside to let me through, and as I stepped to the porch, I noticed that the dog only had three legs. “What happened to him?”

“Got caught in a steel trap,” the boy said. “He was lucky the wolves didn’t get him. That’s how he got his name, Lucky.”

The boy was covered in flour dust from head to toe. He doffed his cap and put his hand out. “My name’s Dan’l Moore. Around here, I’m simply known as Dan. And who might you be?”

“Missouri Cotton. Our wagon’s broke down, and my father sent me for some supplies.”

“So you’re a stranger?”

“That I am.” I handed him my shopping list.

He studied it. “Do you need one candle or a bundle?”

“Only one.” I lowered my head. He and I both knew folks didn’t buy one candle at a time unless they were dirt poor.

He held out the list. “Who wrote this list for you?”

“I did.”

“You can read and write?”

“Fairly.”

“It’s a rare skill in these parts.”

“I was told to ask for the Irishman.”

“He’s my da.” Seeing my confusion, he added, “That’s Irish for father.”

“Do you work for your father?”

“Kind of.” He glanced behind him and lowered his voice. “The truth is that he works for me.” With that said, Dan Moore disappeared into the store.

He returned with a man who could’ve been his twin, only twenty year older and a little stockier. “This is my father, Joe Moore. Everyone calls him the Irishman.”

The Irishman seemed to size me up, and I didn’t like it one bit. The less he knew about my family and me, the better.

He handed my list back to me. “Our wagon grease is out back.” He motioned inside the store. “You can shop until I get back.”

His brogue reminded me of the Irish Channel of New Orleans. As I backed away from him, I couldn’t decide if the Irishman would be a friend or foe. The way my family moved about, he probably wouldn’t be either.

I wandered the well-stocked shelves, absorbed with rolls of fabric stacked along the wall. I picked up the items on my list, carefully watching the door the Irishman had went trough.

Because of my focus, Dan Moore sneaked right up behind me. “Boo.”

I jumped and dropped several items. “It’s not nice to scare folks like that.”

“Wow, I didn’t know you’d be that jumpy. What are you nervous about?

“I’m just new . . . that’s all.” I retrieved my items. “Do you have more family that works here?”

“My younger brother does, but he’s not here today, and my mother does when she’s not sick.”

“What’s wrong?”

“She’s got consumption. ”

I needed to break the awkward silence. “Do you run the grist mill?”

He brushed flour off his shoulder. “How’d you guess?”

I pointed to the line on his forehead where his cap had been. “Your flour line gave you away.”

He smiled, but there was a touch of sadness in his face. Behind us, the Irishman coughed. “Dan, I believe they’re waiting for you at the mill.” He handed the grease to me. “What size nails do you need?”

“A half-pound of eight-penny.”

He disappeared again into the storage room, leaving me on my own.

When the Irishman returned, I plunked my money down on the counter. “We need flour with the money that’s left over.”

He counted my money then measured out the flour. “Anything else?”

“Oh, I forgot. I need a candle.”

“Just one?”

I nodded.

He put two candles on the counter. “Consider that lagniappe.”

“What?”

“A little something extra. That’s what the Cajun call it: lagniappe.”

I picked up the candles. “You can remove some of the flour to make my money come out right.”

“Nah. We’re even enough. Anything else you need?”

“No sir. That’s good.” I stuffed the items into my tote sack.

“Great. If you’re happy, we’re happy.”

“Yes sir. I guess I am happy.”

He walked me to the door, and the way he stared at me made my stomach churn.

I hurried out of the store. To my relief, the Musk and the other men were gone.

A young man leaned against a porch post, using the rough edge like a backscratcher between his shoulders. “Hi yah.” He was one of the Redbones. A little older than me and about two shades darker. “Where you from?”

“Just passing through.”

“Is that your wagon back across Cherry Winche?”

“It is.”

He stepped closer. “My name’s Moon.”

“That’s an interesting name.”

“Moon Perkins, at your service.”

I backed away. “It’s good meeting you, but they’re waiting for me at the wagon.”

He tipped his hat. “Good meeting you, Wagon Girl.”

“How’d you know that?”

“It’s my job to know what’s going on.”

“How’d you get the name Moon?”

“Look at my face. It’s kinda round like the moon.”

“That doesn’t bother you?”

“Heck no.” He laughed. “Been called worse. Besides, everyone’s got a nickname here in Ten Mile. I’ve got a brother named Squirrel and another one who goes by Worm. So for now, we’ll call you Wagon Girl.”

“My folks call me Mizz.”

“Good, for now your Ten Mile nickname will be Mizz the Wagon Girl.”

“What’s Ten Mile?”

“It’s what we call this area. It comes from the fact that most of our people live up and down along Ten Mile Creek.”

“It’s nice meeting you Moon, but I must go.” I hurried away with a wave. Lucky, the store dog, padded alongside me. “Hey girl, which side are you on?”

She wagged her tail.

“You’re probably on the side that feeds you.” She nuzzled my leg. “Well, it looks like I’ve made at least one new friend today.”

I reached the spot where Unk Dial had been hiding but saw no sign of him. I had the lingering suspicion that he was lurking nearby, watching my every step.

Lucky sat on her haunches. When I resumed walking, she trotted back toward the store. “So you’re deserting me? This must be your dead line.” As I scurried down the road, alone with my guilty conscience, a horse’s snort startled me. Caught in the open, I dashed for the cover of the woods.

“Come on out.” It was the Irishman. He dismounted and stood, arms crossed, on the road. Lucky, no longer wagging her tail, stood stock-still beside him.

I stepped out. “Sir, is there . . . something wrong?”

“You forgot something at the store.” He walked to a roadside red oak stump, sat down, and pulled out a pipe, tapping it against the stump. “I’d sure like a good smoke. Mind if I borrow some of your tobacco?”

“Tobacco? I don’t have any tobacco.”

He pointed. “It’s in your left dress pocket.”

Slowly, I pulled out the pack of tobacco and tossed it to him.

He filled his pipe, tamped the tobacco, and lit it. Puffing contentedly, he blew a fine cloud of blue smoke. “It’s not every day that I meet a pipe-smoking girl.”

“I don’t smoke a pipe.”

“Or one your age who dips snuff.” He put his hand out.

I pulled a tin of Garrett’s Sweet Snuff out of my bag and sheepishly handed it to him. “Are you going to have me arrested?”

“Maybe.” He rubbed his chin, watching me squirm. He reminded me of our wagon cat, Claws, torturing an injured mouse. The Irishman never lost his smile or took his eyes off me. I was close enough to notice the color of his green eyes. They were similar to his son Dan’s eyes, except the Irishman’s were what I’d call fierce. Those fierce eyes were doing battle with that kind smile. I wondered which facial trait really defined this man. The answer to that would probably reveal my fate.

“Does anyone else know?” I said.

“Nope. No one but Lucky and me.”

I bit my lip. “Are you going to tell Dan?”

“Dan who?”

“Your son.”

“Well, I heard him tell you that I worked for him, so I guess I’ll have to.” He paused. “No, I don’t plan on telling him unless it happens again.”

“It won’t happen again.”

“I’m sure it won’t.” He grinned. “Why wouldn’t you want Dan to know?”

I felt my face redden. “Oh, I don’t know.”

The Irishman stood quickly, holding up the tobacco. “Now, I promised not to tell anyone, but I do need to talk with your father about this.”

I felt hot tears and ducked my head.

His tone softened. “That is, if you’ve got a father.”

I studied the ground in front of my toes. “He’s the one who sent me to steal.”

“Your father sent you to steal?”

“A good beating awaited me if I returned back empty-handed.”

The Irishman collapsed back onto the stump, puffing so rapidly that the embers flared in his pipe. When he finally looked up, his green eyes were also afire. He tossed the tobacco and snuff at my feet. “You take this on home. Consider it lagniappe too.” He whispered under his breath, “She’s a stranger in a strange land.”

As I shuffled away, he said, “And I’ll expect to see you Monday by eight for work.”

“Work?”

“At the store. You’ll be working off your tobacco stash.”

I stared at him. “Are you serious?”

He mounted his horse. “See you Monday at eight. Don’t come tomorrow ‘cause it’s Sunday.” He whistled at the dog. “Let’s go, Lucky.”

As he turned for the store, I said, “I’m sorry about your wife being so sick.”

He reined in, deep hurt in his eyes. “So am I.”

I watched until Irishman Joe Moore disappeared over the hill. I stood a long time looking in both directions down the trail. Two men were on my mind: Joe Moore and my pap. Comparing them wasn’t fair, but it was hard to avoid.

I picked up my contraband, stuffed it in my tote bag, and walked toward our wagon.

The strangeness of this day made me dizzy. The Irishman’s words echoed in my mind. A stranger in a strange land.

I knew one thing for sure. It was time for this stranger’s life to change. And that was a good thing, because it seemingly couldn’t get any worse.

5

The Store

Pap and Ma were sitting by the campfire when I returned from my foraging mission. I silently handed the contraband to Pap.

“Well?” He grunted. “How’d it go?”

“No problem.”

“Is the store pretty well-stocked?”

“Not as well as it was.” I climbed in the wagon. “I’m pretty tired. I’m going on to bed.”

“You’re not hungry?” Ma said. “I made some fresh corn dodgers.”

“No Ma’am. I’ve kind of lost my appetite.”

It was a restless night with little sleep. The next day was Sunday, and I moped most of the day. I was worried about the reception awaiting me on my return trip to the Hatch and Moore Store. My plan was to spill the beans to my folks before I went to work on Monday. It’s always easier to get forgiveness instead of permission.

* * *

I didn’t sleep much better on Sunday night. Before going to bed, I filled my tote sack with corn dodgers, a small towel, and my books. Before dawn, I hurried onto the footpath and onto the Sugartown road wound through the tall pines. It was a cold morning with a gusty wind that made the top of those pines trees sing. I’d never seen trees this majestic. The thick layer of pine straw reminded me of a thick carpet I’d once walked on in the lobby of a fancy New Orleans hotel.

I started singing/humming that song again,

“In the pines,

In the pines,

Where the sun never shines . . .”

I stopped. Someone—or something—was following me. I stepped behind a tree and picked up a good pine knot. As I suspected, it was Unk Dial.

I threw the knot at him. “What are you doing trailing me?”

He grinned. “I’m squirrel huntin’.”

“You don’t have a gun.”

“Don’t need one.”

“You’re making enough noise to scare off a deaf squirrel.”

He rubbed his bad leg. “My limp makes it hard sneakin’ up. I have trouble getting that laig to do what I tell it.”

“Why’re you following me?”

“Looking out for jaybirds like you is part of my job.”

“How’d you know I’d be out this mornin’?”

“A little bird told me that you might need protection.”

“Was it a jaybird? Why don’t you tell that jaybird I don’t need protecting.”

“Yep, you do.” He pointed to a side road. “About a quarter mile down that road is a turpentine camp. Do you know the kind of men who live and work there?”

He waited until I nodded. “Those are desperate men, and desperate men do desperate things. That’s one of the reasons why I’m keeping an eye on you.”

I increased my tempo. “Well, Mr. Guardian Angel, I don’t want to be late for work.”

He shuffled along beside me and never hushed. He poked my bag. “Whatcha got in your bag?”

“Work clothes.”

“Looks kinda heavy for clothes.”

“I also have my books.”

“You can read?”

“Fairly.”

He shook his head. “I wish I could read. But I ain’t got no book sense. Eliza says I’ll be able to read when I get to Heaven.”

“Who’s Eliza?”

“My niece. She looks after poor ol’ Unk.”

“Can Eliza read?”

“A little. She’s got a lot of the Bible memorized.” He tapped the bag again. “Is that a Bible in your bag?”

“Tell me about the Irishman at the store.”

“Joe Moore? Where do I start? He showed up here about thirty-year ago. Had this story about stowing away from Ireland, landing in New Orleans, and coming here to the Piney Woods.”

“Do you know him well?”

“Sure. I was his first friend in Ten Mile. Took care of him.”

“Kind of like you’re doing me?”

“Yep. I always try to help Outsiders.”

“Am I an Outsider?”

“You are. You kinda look like us Ten Milers, but you and your family ain’t from here. You’re an Outsider and Ten Mile Folk don’t trust Outsiders.”

“Do they trust the Irishman?”

“As much as they can trust any Outsider. Besides, he married into our people. His wife, Eliza, is my niece.”

“So the Irishman’s wife is a Redbone?”

“Dyed in the wool.”

“But their son Will doesn’t look Redbone?”

“Nope, but that’s what he is on the inside. Several of his siblings look as dark as me, but not Will. Unk stopped at the crest of the hill. “This is as far as I’m goin’.”

“You’re not coming?”

“Nope.”

“Aren’t they family?”

“It ain’t them that I’m scared of.” He glanced up and down the Sugartown Road. “It’s those strangers from across the river.”

Unk Dial, a mysterious man in a mysterious land, melted back into the pines. The store wasn’t open yet, so I sat down on the gallery steps and opened my favorite book, The Miserables Volume I. Formally know as Les Miserables, it was written by the Frenchman Victor Hugo. I wasn’t sure of the pronunciation of the book title, and shortened it to Les Miss or L.M. .

The real problem was that I only had the first of the five volumes. I’d pretty well memorized this first installment. My goal was finding the remaining four volumes, but I didn’t hold out any hope in this literary backwater called Westport/No Man’s Land.

I kept loose leaf papers in the leaves of Les Miss. Those papers served as my diary and included about thirty pages of my own version of where I thought Mister Victor Hugo might take the story in those future volumes.

I needed new books to read and that’s why my ears pricked up when Unk said his niece Eliza was a reader. She might have books.

I turned to page 323 in Les Mis. It was my favorite passage where the good bishop buys the paroled convict Valjean’s freedom by lying to the police. As the Bishop tells Valjean, “I’ve bought your soul for God.”

I was so engrossed that I jumped at the sound of rattling keys. It was the Irishman. “Morning. Didn’t mean to startle you.”

I slammed my book shut.

“That’s a mighty big book for a girl your size. You like reading?”

“Better than breathing.”

“What’s that book about?”

“The story of a criminal who tries to leave his past behind and start anew.”

“Does he succeed?”

“I’m not far enough into the book yet.”

“I hope the man in your book does a better job getting past his past than most of us here. It sounds kind of like my own story.”

“Tell me more.”

He turned away. “Not now. Maybe some other time. Now I warn you: there won’t be much reading at the store.”

“No sir. I just brought it for safekeeping.”

“Safekeeping?”

“Yes sir. We live in a wagon, and I’m always afraid something, or someone, might tear up my books.”

He pulled out his pipe. “By the way, you don’t have any tobacco on you, do you?”

I fumbled in my pockets. “Doggone if I didn’t leave it at home.”

He laughed. “I bet you did, Smokey.” The Irishman un-bolted the doors. “If you work hard today, it’ll pay off your tobacco debt to Hatch and Moore.”

I was eager to change the subject. “Did you know President McKinley died?”

“No. I knew he’d been shot.”

“Yes sir. He died a couple of weeks ago. Chester Arthur’s our president now.”

“Out here on the frontier, it really doesn’t make much difference who’s president.” He

tossed me an apron and brush broom. “Now, get this gallery cleaned off.” He stopped at the door. “If you see anything . . . uh, suspicious, let me know.”

“Like what?”

“Anybody hanging around, drinking, looking for trouble.”

I pointed to Unk, who was sitting in a grove of young pines. “Suspicious, like him?”

The Irishman waved. “Don’t worry about him.”

“You trust him?”

“With my life.” He stopped at the door. “And so can you, Smokey.”

I didn’t care for my nickname but knew I’d earned it. “How long are you going to call me Smokey?”

“Long as needed.”

I was putting two and two together with my own suspicion: the Irishman and Unk were in cahoots. They were looking after me. It both irritated and flattered me. Someone, besides Ma cared, and sometimes Pap, cared about my well-being. I knew Pap loved me. He just didn’t quite know how to show it. Sadly, neither did I.

I finished sweeping the gallery, then moved to the yard. I’d always thought of myself as an artist, so I swept the dirt in geometric lines and circles.

Dan Moore walked up. He eyed my artwork in the dust. “That looks like a snake.”

“Could be.”

Dan grinned. “Da doesn’t like snakes.”

“Who does?”

“No. He’s deathly afraid of them. It’s the Irish in him; You know, that Saint Patrick story about throwing all the snakes and devil out of Ireland.”

“Do you believe that?”

He shrugged. “Daddy says they don’t have snakes there. Claims Saint Patrick tossed them out and they all landed in Louisiana.”

“How many are there?”

“Snakes?”

“No, in your family.”

“Well, there’s me and then there’s my younger brother, Will. My older brother Mayo lives in Alexandria, and my older sister lives in Shreveport. Three of my siblings didn’t survive childhood and are buried at Oak Hill Cemetery.

“Does Will work at the store?”

“Not right now. He’s on house arrest.”

“How so?”

“Last month we had a Brush Arbor Revival over at Occupy Church. Folks came in their wagons and the mothers with babies made sure their wagons were next to the arbor. When the babies dozed off after feeding, the mothers laid them down on quilts in the wagon bed. My brother Will and some other scalawags sneaked around in the dark and switched four of the sleeping babies. Mothers didn’t realize they had the wrong baby until late that night or early the next morning. It took a full day untangling everything and getting the babies back in their correct home.”

“That’s bad.”

“It was an ill-fated kidnapping, and the fur did fly. As you can imagine, Will ain’t the most popular boy in Westport right now.”

“You weren’t in on the baby-swapping?”

“No way. I like a good prank but knew not to cross the line. Those mommas were like grizzly bears robbed of their cubs. Da whipped Will good and put him on probation for the month. He’s got double chores and isn’t allowed to go anywhere without Da or Momma.”

Dan tipped his cap. “I’d better get back to the mill and get to gristing.”

I spent all morning cleaning around the outside, using the brush broom to attack the spider webs on the walls and eaves. Twice that day, I stuck my head inside and offered to help, but the Irishman gestured me away. It shouldn’t’ve surprised me. I wouldn’t want a five-fingered discount thief in my store either. Well, at least I was working off my debt.

At lunch, I sat on the porch with my corn dodgers and book. I was surprised when Dan Moore brought me a plate of beans and cornbread.

“Here’s some victuals.”

I held up a cold corn dodger. “I’m fine.”

“That johnnycake can’t compare to beans and cornbread.”

“What’s a johnnycake?”

“It’s what you’re holding.”

“We call it a corn dodger.”

“Well, regardless of what it’s called, it don’t stack up against a hot meal.” He handed me the plate.

I didn’t even bother being ladylike. I ate without taking’ a breath. It was hot and delicious and I was some kind of hungry. “Who made this?”

“My mother.”

“She can cook.”

“She is. She’s been really sick but can still cook up a storm on her good days.” He handed me another piece of cornbread. “The women in our Redbone culture can cook.”

Between a mouthful, I said, “I still haven’t got a handle on what a Redbone is.”

Dan lowered his voice. “Let me fill you in. Be careful using that term, Redbone, in open conversation. Some of them take deep offense at the word. They usually call themselves Ten Milers, so that’s what I call them. If you say Redbone, they might come at night and burn your pine knot pile.”

I glanced around. “Okay then, what’s a Redbone?”

“My Momma says that the real question is, ‘What’s not in a Redbone?’ We’re a gumbo mixture of all kinds of groups that have settled in this No Man’s Land. My kin can’t even agree what strain of Indian blood flows in us: Apache, Attakapas, or Caddo.”

“Your mother sounds like a real character.”

“She’s one of a kind and has a full dose of the Outlaw Strip in her blood.”

“You sound proud of that?”

“I am.”

“You’re proud of being called an outlaw?”

“I’m proud of our independent spirit. We’re rebels. It’s the defining mark of Ten Mile. You’ve probably noticed we’re a little standoffish to Outsiders.”

“What about your daddy, the Irishman. Is he an Outsider?”

“Dan, what about you?”

“Look at me. I look Irish, but I’m a Ten-Miler on the inside. I wonder if I’ll ever fit in here. Folks do judge a book by its cover. I’m afeared they’ll always view me as an Outsider.”

He placed his arm beside mine. “You’re dark enough to fit in as a Ten Miler. What are you?

“I’m not sure. My parents refuse to talk about their past.”

“You don’t have family?”

“Nope. I had an older sister named Helen, but she died of yellow fever while we were in New Orleans. I barely remember her.”

“No grandparents?”

“None.”

“No uncles, aunts, cousins?”

“Nary a one.”

“Wow. That’s sad. What about sisters and brothers?”

“All of them died in our wandering. All I know is that my folks met somewhere in the Carolinas. Ma—who’s dark like me—is a Mulungeon.”

Just then a large calico cat scooted past me.

“That’s Esther,” Dan said. “She runs the rat department here at the Westport Store.”

“She looks healthy from all appearances.”

“I think she’s great with child. Or in her case, kittens.”

I nodded at the sign on the storefront. “This store is the Hatch and Moore Store, but you just called it the Westport Store.”

“Westport is from Da is from. It’s a seaport town in County Mayo, Ireland. He gave this place the name after we built the store.”

Your father is Moore, so who is Hatch?”

“Captain Hatch was with my daddy in the war. They served with the quartermaster’s corps at Vicksburg. Hatch lives in Alexandria and is a silent partner in the store.”

“Why’d they open a store in the middle of the woods?”

“Because there’s nowhere to buy supplies between Hineston and Sugartown. It’s a full day’s wagon ride to either town, so this was a logical place to set up shop. The only problem is that the store is considered an Outsider’s venture.”

“So your daddy is worried about some kind of trouble?”

“There’s deep tension between the whites trespassers and the locals. It’s simmering over grazing rights, timber, and land. There’s been talk of bushwhacking and burnouts. Everyone’s on edge.”

“What’s a bushwhack?”

“An ambush. A specialty of my people.”

“You say ‘your people.’ Which side are you on?”

“Both and neither.”

“What will you do if fighting breaks out?”

“I’ll try to keep my head down.” His shoulders sagged. “I hope I never have to make that choice.”

I had noticed a stack of coffins in the corner of the store. I pointed at them. “Have much need for these?”

Dan led me to a closet. “Look there.” There were several child-sized coffins. “Sadly, we sell as many of those as the big ones.”

“Life seems fragile and short in No Man’s Land.

Before he could finish, the Irishman walked onto the gallery. “Daniel, you and uh, Missouri, better get back to work.” After his son left, he whispered, “I won’t call you Smokey anymore.”

“I appreciate that.” It dawned on me that this man seemed to take a real interest in me. “Tell your wife that the beans and cornbread were wonderful.”

“Will do.”

Customers trickled in and out during the afternoon. I busied myself keeping the porch and yard swept, and as my custom whistled while I worked. Time flies by when you’re working and whistling, and I’m an unreformed whistler.

The Irishman walked out on the porch. “A whistling and a crowing hen . . . both will come to a very bad end.”

I leaned on my broom. “I’ll try to remember to silence my whistler.”

“Just picking. Whistle away. It’s a free country.”

Lucky limped up to the Irishman. He nudged its ears. “Lucky, have you had a good day?” He turned to me. “Lucky’s a fine dog, but has one big problem: he’s afraid of loud noises. Anything loud, be in thunder, gunfire, or fire poppers, sets him into a panic.”

The Irishman nodded at the setting sun behind the pines. “Missouri, you’ve done a good day’s work. As far as I’m concerned, we’re even. You’ve paid your debt. You better hurry on before this short day catches you out in the open.”

“I’m still sorry about what happened.”

“It’s in past. Wasn’t your fault anyway. Let me give you a word of advice: don’t stumble over anything behind you.” He held out an envelope. “This is for later.”

“What is it?”

“Lagniappe.”

“Thanks. I do have one favor to ask.”

He nodded. “Go ahead.”

“I . . . I’d like to come work on Monday. You could pay me in food or supplies. I believe I’d be good help, and to be real honest, we need money something bad.”

He rubbed his chin. “Well, I like the way you worked, and I’m prone to believe you won’t have any more sticky fingers.”

I dropped my head. “You can trust me, Sir.”

He studied me closely, then smiled. “Well, we’ll find out. See you Monday morning bright and early.” He walked about five paces, then stopped. “And remember, don’t stumble over anything . . .”

“Behind you.”

He waved. “Forward. Always forward.”

I stepped off the porch and was startled to see Pap wobbling toward the store. I hurried to him, wanting to keep him as far from the Irishman as possible.

He was roaring drunk and slurred his words. “Where’ve you been?”

“Helping out.” I handed him the envelope.

“What’s this?”

“My pay for the day from the store. It’s a dollar.”

He grabbed my arm. “How’d you get a job at that store?”

“It’s a long story, but the bottom line is that I made some money for us.” It sickened me to give my hard-earned pay to him, but it beat a black eye.

He held it up to the light. “It’s counterfeit. In fact, it’s one of the dollars I sent with you yesterday.”

I thought about a verse in Proverbs, Whoso diggeth a pit shall fall therein, and he that rolleth a stone, it will return upon him. The stone had rolled back on us. I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or cry. Did the Irishman do this, or was this simply coincidence?

Pap staggered toward the store. “I want to see this store for myself.”

“Pap. It’s closed. Let’s go home.” I eased him in the direction of our camp site.

As we walked in the last daylight, I glimpsed a figure slipping along behind us. I was pretty sure it was Unk Dial.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller