Today we begin featuring a weekly audio podcast to supplement Tuesday’s blog post. I believe you’ll enjoy my reading of “The Landmark Pine.” Download free here.

A word from Curt

Home.

It’s a good word. But at this season of my life, it’s a complicated word. Where is home for me? We’ve just returned from a wonderful month in Louisiana. Great time with our family. So grateful for the many American blessings we have.

We were home. The Louisiana Piney Woods where my roots go deepest.

At the same time, my heart ached for Africa. It’s been our home for two years. As we returned to Africa (Houston to Istanbul, Turkey then Rwanda and finally Uganda) I felt at home.

But I’m also missing home. It’s where my family and heritage is.

I’m writing this week about the two homes I currently have. The land of the tall Louisiana pines as well as Red Dirt Africa with its palm trees.

They say home is where the heart is.

My heart is currently comfortable in two places. That’s a good thing but also a confusing one.

Join me on the journey as I write about the culture adjustment of returning to Africa.

“No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.”

Last night, I listened to the audio podcast of this story.

I wept as I reached the end.

Part of it was due to the emotional tangled feelings of leaving family (again) after a month in the US.

Maybe it was jet lag.

But near the end of “The Landmark Pine” audio, I cried. It was due to loss.

Listen to the audio for yourself. Read the story below. Pay attention to tomorrow’s followup blog post and you’ll understand the source of my emotion.

Download Audio Podcast of “The Landmark Pine.”

The Landmark Pine

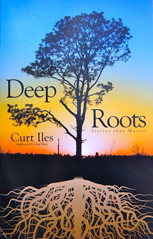

It’s the lone pine tree featured on the front cover of our short story book, Deep Roots. It’s a landmark tree, a special type of tree tied to the history of our area.

The early pioneers used these trees as waypoints for wagon trains and travelers.

The landmark pine on the cover of Deep Roots is along the Longville-Dry Creek Road, commonly called the “Gravel Pit Road.” It’s a winding eleven-mile track that has only recently been paved.

I love traveling this road because most of it is pine woods bisected by three creek crossings: Dry Creek (twice) and Barnes Creek. Due to the seclusion of the road, it is prime territory for spotting wild turkey and deer.

Before we drive from Dry Creek to the Landmark Tree, it’s time for a short lesson.

The early settlers in America knew about landmark trees. A good example of this is the community of Lone Tree, Iowa. It derives its name from a giant elm that grew nearby in the pioneer era; as the only tree between the Iowa and Cedar Rivers, it served as a prairie landmark. It served as defining point in that area until its death from Dutch Elm Disease in the 1960s.

In Piney Woods Louisiana, the timber clear cuts of the early twentieth century left only a few pines standing. These trees naturally became useful as landmarks for travelers as in, “The road turns left over thar just past that big pine.”

Traveling west from Dry Creek toward the Landmark Tree, you pass two of the finest preserved dogtrot houses in Louisiana: The Fanny Heard house, followed by the Mary Jane Lindsey home place.

Just south of the Lindsey home is where my first Dry Creek ancestors homesteaded in 1848. Andrew Jackson Wagnon and Nancy Fulton Wagnon traveled from Georgia to stake their claim in the No Man’s Land. They homesteaded in the edge of Dry Creek Swamp near a free-flowing spring.

A few years ago I walked the entire Gravel Pit Road. As I walked over the hill and down toward the swamp, I was overwhelmed that this was probably the same path A.J. Wagnon walked when he left for the Civil War.

He never returned, dying near Opelousas, Louisiana of Typhoid Fever. His wife Nancy lived on the homestead until her death nearly forty years later. The Wagnon descendants are scattered all over the Piney Woods.

Continuing toward the Landmark Tree, we pass the site of the one-room Mt. Moriah School. It’s where my ancestors walked to school during the nineteenth century. I have a photo of the thirty-member student body gathered in front of the one-room school. It was nicknamed the “Hen Scratch School” due to chickens scratching around the yard where the students ate their lunches.

The Landmark Tree stands on the north side of the bumpy road as we enter the secluded part of the trip. We’ll stop by it and talk more on the return trip.

After crossing Dry Creek the second time, we pass over Grave’s Gully. If you walk south along it, you’ll come to the Jayhawker graves.

Two local men, William Washington Green and Lemuel Jackson Bradford, were ambushed and murdered by jayhawkers in 1865. This spot is a reminder that our area’s nickname of “The Outlaw Strip” was well-deserved. Even now a visit to the two lone graves has an eerie feel to it.

To the north of the main road is the abandoned gravel pit. For a generation, truck after truck of gravel and pebbles were mined from the pit. I remember my father trying to get Wildlife and Fisheries to stop the gravel pit from dumping its wastewater into Dry Creek.

It was my first time to understand about conservation, stewardship, and a love of the land. Although his campaign was unsuccessful, I’ll always admire his stand.

Soon the traveler crosses over Barnes Creek, still thirty winding miles from its junction with the Calcasieu River. Looking at the creek now, it’s hard to fathom how log rafts were once floated to the sawmills on Lake Charles.

Closer to Barnes Creek’s mouth is where another branch of my family arrived in the early 1800s. Most of them are buried at one of Louisiana’s most beautiful graveyards, Lyles Cemetery between Bel and Topsy.

The Gravel Pit Road climbs out of the swamp and back into the pines as it nears the once thriving sawmill town of Longville. Long Bel Lumber from Longview, Washington operated a large mill during the cutting of the virgin pine forests that had stood for hundreds of year.

In the “cut out/clear out” philosophy of the times, all of the pines were cut. Very few landmark trees were left.

Let’s double back and stop for a talk under the Landmark Tree.

Dry Creek, LA

Another name for these lone trees were “seed trees.” These were trees spared during the lumbering for the purpose of providing a source of seed for re-stocking the over-cut areas.

The longleaf pine has huge pine cones which contain the small seeds that can grow into trees. Sadly, very few were left. The result was a stump-filled expanse of grassy land. My great-grandfather, Frank Iles, told of walking from Dry Creek to Reeves and being able to see for miles. He told of constantly being on the lookout for wild bulls due to the lack of trees to climb for escape.

Another name for the lone trees left behind is “witness trees.” As the original public land surveys were done in the early 1800’s, every section and quarter section were marked by nearby witness tress.

My father was a land surveyor. In seeking the corners of land parcels, he’d look for the witness trees. They normally had a large X cut into the bark with an ax. I’ve seen Daddy dig futilely for the stump of a long gone witness tree needed to clearly mark a corner.

# # #

There’s an additional meaning of witness tree. It refers to an old tree that witnessed a historic event and still stands as a silent testimony.

The Gettysburg Battlefield is a hallowed spot for all Americans. On Culp’s Hill where the Union fortifications helped ensure victory over the confederates stands a witness tree.

It was there during the fierce three days of battle in July 1863. A few weeks later, famed photographer Matthew Brady took a photograph showing two of his assistants sitting on a rock by the tree.

That tree still stands today as a witness to how our nation’s history hung in the balance. It’s a witness tree of history. Our American history.

My research led to other stories of landmark and witness trees. In cases of famous trees toppling in a storm or from old age, it was reported as if a death in the family had occured. The passing of a landmark tree calls for mourning.

I wonder if I’ll see the demise of the Gravel Pit Road tree. It looks pretty sturdy. I hope it outlasts me. I also hope to one day take a great-grandchild to see the tree.

It’s rode out several strong hurricanes in 1918, 1957, and 2005. In the photo, you can see where it lost a limb on the left during Rita.

It’s a large landmark tree with strong roots. As this book went to print, my son Clint measured its diameter at 29 inches. He took out his increment bore and drilled into its core. He estimated its age at least seventy-five years, maybe more. As I examined the pencil-sized core, the sweet aroma of pine sap filled the truck cab.

It’s a worthy landmark tree, but it’s not the Louisiana Landmark Tree. That designation belongs to the twenty-eight live oaks forming the entrance to Oak Alley Plantation along the Mississippi River. They predate the 1718 founding of New Orleans and are majestic to see.

Don’t tell the folks at Oak Alley, but I wouldn’t trade a hundred live oaks for the Dry Creek Landmark Pine. It marks the area that I call home. That’s why I wanted it on the cover of Deep Roots.

It marks a spot. A spot that my heart calls home.

It’s also a seed tree.

During its long fruitful life, it’s provided seeds and pollen for new trees in the surrounding area. Younger trees have been grown, thinned, cut, replanted, and cut again. All that time, the landmark tree has watched in its place of honor along the old fencerow.

I guess it’s kind of like a proud grandpa or great grandpa. It’s survived the axes, crosscut saws, chain saws, and hydraulic shears of generations of Louisiana timber men.

It’s a witness tree. A reminder of the legacy of the longleaf pine that defines western Louisiana. Our economy, our culture, even our philosophy is tied to this tree.

A lone landmark pine standing proudly alone in the heart of Beauregard Parish, Louisiana.

Long may it stand.

Download audio of “The Landmark Pine.”

Join us tomorrow for an update on the Longville Gravel Pit Road Pine.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller