Al, the FEMA Gator Man

“Amos Moses was a Cajun.

Lived by himself in the swamp.

He hunted alligators for a living,

Just knock them in the head with a stump.”

–“Amos Moses”

Jerry Reed

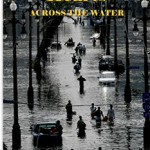

He was the first federal official I met in the days after Katrina. Our New Orleans evacuees had the same question day after day, “When is FEMA coming?” I would return from our daily Emergency Preparedness meetings with no good answer for their inquiries.

Here they were stuck out in the piney-woods loneliness of Southwest Louisiana at a non-Red Cross-approved shelter. I know they thought they’d never see a federal official. I was nearly starting to think the same thing myself.

So on the day when these first two FEMA workers got out of their car to visit the City of Hope, I was elated. They quickly informed me that they were lower echelon personnel with no real information, $1,500 debit cards, or proclamations to share.

I immediately liked them for their smiles and openness. It was nice to hear someone just be honest. One worker was named Pam and the other introduced himself as Ellsworth Cobble. Their accents gave them away as upper Midwestern United States. Pam was from Indiana. Ellsworth Cobble was from Chicago. I nearly knew it without his admitting it.

Their blue shirts and official nametags with ID pictures made them look very official and important. I quickly escorted them to the dining hall where most of our evacuees were. The majority of our evacuees had already found jobs and were working out in the community today. However, I wanted those present with us to meet “FEMA.”

A quickly convened crowd followed them into the Dining Hall and excitedly gathered. Pam repeated their assertion that they had no big news or funds to give, but had simply wanted to let our evacuees know they were not forgotten and help was coming.

You never know when a crowd can turn into an ugly aggressively verbal mob. I knew how badly many of these evacuees were hurting for cash and reassurance. But instead of any angry retorts, the evacuees seemed satisfied that help was coming. The sight of live FEMA employees in the wilderness of Dry Creek was proof enough that help was coming.

Ellsworth Cobble, who looked to be in his early sixties, stepped forward. I wondered how his Chicago accent would go over with the “Who Dats” and “Boudreauxs” gathered around him. Even his name—Ellsworth Cobble—sounded Chicagoan.

But he introduced himself by saying, “Hi, my name is Al and we’re here to help you. I’m just a worker bee and not really important, but we do want to help.” Ellsworth, I mean Al, and Pam did help by doing what these folks needed the most: simply listening.

Each evacuee present told their story… one by one… sad detail by detail. Al and Pam listened… and sincerely replied along the lines of, “I’m so sincerely sorry this has happened to you and we are going to try to get the help you need.”

I’m positively sure their listening was sincere and open. There are some things you can fake, but being a good listener is not one of them. A person’s inflection, eye contact, focus, and non-verbal gestures all tell you about what their mind and heart is. There was no doubt to these displaced New Orleanians that Al and Pam’s ears and hearts were right there with them.

Right there I made up my mind that I liked these two, and what anyone had to say about FEMA, the organization, and its tangled disorganization, just didn’t hold water on these two.

Sadly, we never saw Pam again. She had to return to Indiana for a family emergency. But Ellsworth “Al” Cobble kept crossing our path in the days and weeks to come. He always had that smile and kindness about him that I knew would connect with the good people of rural SW Louisiana.

I saw Al four days before Rita came to our part of the state. He had now been in Louisiana for over two weeks. He greeted me with the statement I love to hear from visitors, “I can’t wait to get home and tell my friends about the good people of Louisiana.” In spite of Katrina’s wrath, or maybe because of it, Al had seen the generous and giving side of our state. That made me happy.

But on this Monday before the next storm, Al had a tale to tell. He excitedly started in his thick Chicago gangster accent, “You’ll never believe what I did this weekend! I went alligator hunting.”

He began this story of making friends in Johnson Bayou, the westernmost community along the Louisiana Gulf coast. In great detail he told of riding through the marsh in an airboat and the thrill of hurdling levees at thirty miles per hour and tearing through the tall fields of marsh grass at full speed.

But he saved his best descriptions for the actual capturing of the five ‘gators his hosts had caught. There was no detail left out as he described the thrashing about of the huge ‘gators on the bait hooks and how they let him shoot three of them himself with a .357 pistol.

“They pulled one large gator on board…it was about ten feet long. I believe they purposely threw it over by me. Its big tail was still whipping about and I thought I was going to have to jump overboard!” I could just see his good-humored Cajun hosts laughing heartily at FEMA Al’s excitement. I told Al, “Well, I hope you got some pictures of your alligator hunt because no one in Chicago, even your wife, will believe your story.”

Al smiled, “Oh yes sir, I’ve got it all on film.” He sidled up to me and elbowed me as he smirked, “I’ve got a good friend in Chicago that loves to brag about his fishing exploits. He’s always caught one bigger than everyone else. My friends in Johnson Bayou helped me out by propping up that biggest ‘gator and taking a picture of me grimacing fiercely as I held it in a headlock. I bet my bragging friend won’t be able to top that.” All of us gathered around and laughed at the idea of FEMA Al wrestling down the big ‘gator.

I only saw Al once more. It was after Rita at an emergency-planning meeting in the dark days after the storm. I pointed him out to some FEMA big wheels that had arrived to help out. I asked them, “Do you guys know that small older fellow in the Blue FEMA shirt over there?” They said they’d never seen or met Ellsworth Cobble. I said, “That’s Al. He’s been here with us for over three weeks. He is one of your best goodwill ambassadors.”

Before leaving, we talked once more. We both lamented that his friends in Johnson Bayou had probably lost everything. The eye wall of Rita came ashore just west of this Cameron Parish community. Early reports told of total destruction of the homes, churches, and schools of Johnson Bayou.

I think of Al when I see news reports about lower Cameron Parish and how the coastal marsh areas had been destroyed. I wonder about the alligator population and the fishing. I worry that the large oaks at Peveto Woods, one of America’s greatest birding sites, are gone.

I can see Al showing his ‘gator-hunting pictures to his Chicago friends. I’m sure they’ll have a hard time believing a place like Southwest Louisiana really exists. I know FEMA Al will also tell them about the good and gracious people of Louisiana, from an area knocked down and torn down by a storm named Rita—an area where the people will return, repair, rebuild, and re-establish their way of life.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Another great piece of writing. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Jessica. Your kind words are appreciated and spur me on to write more and better.

Curt

Thanks Jessica.