The Evening Holler

This is the first story from my first book, Stories from the Creekbank.

Over thirty years later, it is still my most requested story.

You can hear an audio version of the “The Evening Holler read by the author, at the Creekbank Podcast as well as Spotify.

Our YouTube Channel episode comes straight from my rocking chair on the porch at the Old House in Dry Creek.

Enjoy! Please share! Thumbs up and ratings are appreciated.

C.I.

The Evening Holler

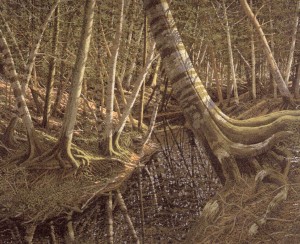

I sit in the woods on a cold still October morning. This is my favorite time of year when the weather becomes cool and the sky is usually clear. As daybreak comes across Crooked Bayou swamp, it is so still and quiet.

A mile through the woods I hear a neighbor’s roosters crowing.

In another direction I hear my brother-in-law loudly scolding a dog.

It’s amazing how sound carries so distinctly in the woods.

As it gets quiet again and I shift on my deer stand, a lone owl gives his eight note song. Soon he is joined by another sentinel way across the swamp.

These two barred owls converse back and forth in their unique eight note call: Hoo hoo-hoo hoo, hoo hoo-hoo hoawww”.

Always when I hear this owl I recall old-timers describing his call as, Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you-alllll?”

Listening to the dueling owls, I’m drawn back to one of my favorite stories of the settling of our community.

I call it the story of “The Evening Holler.” My great grandparents, Frank and Dosia Iles, told me of this event. This unique call, a tradition going back to the pre-Civil War settling of the Dry Creek area, was a primitive means of communication among these early settlers.

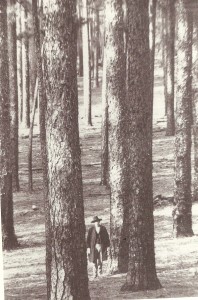

The first white settlers in Dry Creek lived in the woods along the creeks and streams. They were surrounded by vast tracts of pine forests.

This area of Southwestern Louisiana was a neutral strip claimed by both Spain and the United States. There was no law and a sparse population.

Later on when there was law, the nearest officer was in Opelousas over seventy miles away. Indians, though friendly, stilled roamed the woods. Bears and mountain lions were common in the swamps.

Because these pioneers were homesteading tracts of land, they seldom built homes right next to each other. They were forced by necessity to depend on each other. So they developed an ingenious method of checking on the welfare of neighbors.

Late in the evening at dusk, each man would stand in the yard or on the porch of his home. Just as the sun dropped behind the wooded horizon, the ritual would begin.

Each man would begin hollering his own individual yell.

Each of the pioneers had his own unique hollering style- easily recognized by his own pitch and voice. The closest neighbor would answer back.

He would be joined by the next neighbor down the creek. As the evening holler passed down through the woods, each man would then be assured as to the well-being of his neighbor as he heard an answering yell in return.

In spite of the distance between home places, the hollering carried for long distances.

Remember, this was a time before televisions, air conditioners, or vehicles. There were fewer artificial sounds to drown out the evening noises. If you’ve ever really been out in the woods, you’ll understand what we mean when we call it “an eerie silence.”

My ancestors told me of how if a man did not hear the call of his neighbor, he would holler several more times at different intervals. If he still did not receive a reply, he’d go check on his neighbor. My great-grandmother told of seeing her father saddle up his horse to go check on a neighbor who did not answer. Even though things were usually fine at the neighbors, he went each time to double check.

To him it was simply a matter of being a good neighbor. These early settlers took care of each other. The evening holler was kind of an early version of today’s Neighborhood Watch.

Sometimes when I’m enjoying the quietness of a fall sunset, I’ll hear those owls begin calling to each other across the woods.

Or in April, I’ll listen to the whip-poor-wills as they answer each other with their own version of the evening holler. It’s at times like this that I think about the evening holler and what it meant . . .

It reminds me of how our ancestors took care of each other. They truly considered a neighbor . . . a neighbor.

In our modern busy crowded life, we seldom know our neighbors; much less check on their well-being.

Even with all of our marvelous modern communication tools, we usually know much less about our neighbors than our ancestors did.

As I sit here thinking about these things and how much we’ve lost in “neighborliness,” my neighbor, Joe Watson, drives by in his truck.

He honks as he sees me sitting on the porch. His truck is loaded with firewood. All fall and into winter, he cuts firewood for the widows and needy of our community. He’s on his way with a load to give someone right now.

Then the thought hits me: maybe the evening holler isn’t as dead an art as I think it is.

Then I recall another neighbor who daily checks on an elderly woman who lives alone. He makes time to take care of this person. Then I think of my parents who’ve always picked up the mail and check in daily for another home-bound senior adult.

I remember times, when after a house fire in our community, people have banded together to supply needed items and volunteer to help rebuild the home.

I recall the time-honored Southern tradition of supplying food to families who’ve had a death. We have a deep respect for death and that is how we carry out our unique traditions of respect and kindness.

As I think of each of these, and many more I could name, I realize how much good and caring there still is in people.

Yes, times have changed.

We don’t live in as close contact with our neighbors as we should.

Here in the 21stAs humans we need to take ownership on the care of our neighbors. It is a decision that each of us can choose to do.

It is a positive decision that many of my community neighbors have chosen to do.

As I take time to really look, I still see the spirit of the evening holler alive and well in a small community I love called Dry Creek.

“The Evening Holler” comes from my first book, Stories from the Creekbank. All thirteen of my books can be found on Amazon.

My updated version of “Evening Holler” can be found on our You Tube channel.

as well as an audio rendition at our Creekbank Podcast or Spotify.

When you visit those sites, please subscribe as well follow.

-C.I.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Great story to read again. I remember how my daddy could holler. His voice could carry for miles. He could holler the boys out of the woods from hunting. . Great topic.

Alda,

Aren’t we products of a neat time and place!

I love this! I remember my Granny Amy and Aunt Rose hollered across ten-mile creek when there was a phone call for them ,at Spencer Willis’s house. The only family in the area with a phone. So my Granny would walk to the creek to meet Aunt Rose and they would walk to Mr.Spencer’s home ,together. Down hog trails and no night lights.

That’s neat Shirley. Didn’t we grow up in a good place and time.