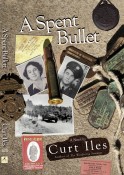

Printed below are chapters 1 and 2 of our novel, A Spent Bullet.

You can learn more at http://www.creekbank.net.

Also, keep in touch through Facebook (friend page Curt Iles and fan page Creekbank Stories and Curt Iles) as well as Twitter.

Part I

The Battle for the Bullet

“I want the mistakes made down in Louisiana, not over in Europe.

If it doesn’t work, find out what we need to make it work.”

– General George C. Marshall

Chief of Staff, U.S. Army

Spring 1941

“Monday I go to Louisiana . . . The old-timers say we are going to a God-awful spot complete with mud, malaria, mosquitoes, and misery.”

– Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower

August 5, 1941

Chapter 1

The Bullet

“How unhappy is he who cannot forgive himself.” – Publilius Syrus

Wednesday, August 13, 1941

DeRidder, Louisiana

Elizabeth Reed had only met one soldier she liked, and he had wounded her deeply. So when the blond G.I. tossed the bullet, she didn’t flinch even as it landed at her feet.

The soldier leaned out of a crowded Army truck. “You’re beautiful. Write me.” He pointed at her feet. “The bullet—write me.” The empty cartridge had a note folded inside. The bullet-tossing practice was called “yoo-hooing” and was an attempt to get the attention—and addresses—of local girls.

A loud wolf whistle from the truck grated on her like fingernails across the slate board in her classroom. The same soldier called out, “I’d love a kiss from a pretty Southern girl like you.”

Elizabeth coolly nodded at a large matronly woman near her. “Are you talking to me or her?” The troop truck exploded in laughter. She fanned away the dust. “Soldiers. They’re all the same.” Traffic began moving and the smoking truck rattled across the railroad tracks. Her ten-year-old brother Ben, behind her, had missed the tossed bullet. He spied it just as Elizabeth drew her foot back to kick it. “What’s that?”

“A soldier threw it. It’s a note stuck in an empty cartridge.” As he knelt, she pulled him away. “Leave it alone. It might blow up.”

“Lizzie, you’re playing with me.” He bounced on his toes at the three-o’clock train’s whistle. “They’re here.”

Yelling from the convoy’s last truck replaced the whistle. Elizabeth clamped her hands over Ben’s ears. “Sometimes what they say isn’t for fresh ears.”

He twisted loose. “My ears ain’t fresh.”

“Benjamin Franklin Reed, you’re impossible. It’s aren’t—not ain’t.”

“Well, either way, my ears ain’t fresh.”

A soldier yelled from the truck, “Is this Detroit?”

“Nope, this is DeRidder, Louisianer.” Ben had always been allergic to silence.

Elizabeth bent down. “We live in Louisiana, not Louisianer.”

“Ain’t that what I said?” His face was pinched. “Is this how you’ll be treating me in your classroom?”

Grabbing him in a playful headlock, she goosed him until he said, “Uncle.” Elizabeth looked up at a tall grinning soldier. “I’ll wrassle you next if you’re through with him,” he said in a rich west-Texas drawl.

She felt her face flushing. “I believe I could whip you too.” She grabbed Ben’s hand. “Come on. Our train’s here.”

“Where are y’all going?” Texas said.

She cringed when Ben said, “We’re here to pick up some chicks.”

The soldier laughed. “Well, count me in.”

Elizabeth pulled on Ben’s shirtsleeve. “Let’s go before the train leaves.”

He knelt on the sidewalk. “But what about the bullet?”

“Leave it.” He was slowly rolling the cuff of his overalls. “Come on Ben. A dollar’s waiting on a dime.”

He scampered forward. “Poppa says that there are three things a soldier likes best: dogs, kids, and pretty girls.”

“In that order?”

“Probably not.”

“Well Ben, which one are you?”

“I’m not a dog or a pretty girl, so I guess I fit in as a ‘kid.’” He squeezed her hand. “And if I eyed those soldiers right, you definitely fit the ‘pretty girl’ part.”

“You think so?” She hurried on ahead.

Ben stepped in front of her. “Lizzie, are you mad at me?”

She froze. “Why would I be mad at you? I love you like a son.” She licked her fingers, trying to tame the unruly cowlick in his dark hair.

“But I’m your brother, not your son.”

“You’re ten years younger than me, so I guess you’re kind of both.”

“You seem mad at someone. Is it those soldiers?”

She drew in a long breath. “I’m not mad at them . . . just tired of them.”

“Is it ’cause they’re men?”

“Who’s been talking to you?”

“Well, Peg said . . . some soldier hurt you.”

“Is that so?”

“She claimed being your twin lets her see into your heart—says you got wounded by a soldier—said you were eligible for a Purple Heart.”

Her jaw tightened. “Maybe a broken heart, but not a purple one.” She looked around. “Peg said she’d meet us here before the train arrived.” As they neared the depot, she rubbed Ben’s ear. “Watch for those army trucks.” He was digging in his pocket, so she repeated, “Watch for those trucks.”

“I will.”

Her twin sister Peg’s words hung like the dust in the air. Hurt by a soldier. Wounded. Elizabeth heard her own voice bouncing in her soul. It’s your own fault. You don’t have anyone to blame but yourself.

She bit her lip. It would not happen again.

Chapter 2

Bad News

CLOSE VOTE EXTENDS SERVICE TERM FOR THOUSANDS OF SOLDIERS

(Washington) By a vote of 203-202 yesterday, Congress removed restrictions pertaining to federalized National Guard units. This close vote means National Guard soldiers will have their terms extended and may be moved to locations outside the United States.

Private Harry Miller had never hated a place like he hated Louisiana. As his National Guard convoy reached the end of the paved road outside DeRidder’s city limits, he braced himself for the teeth-jarring washboard road. Through the chalky red dust covering them, Harry scanned the bleak cutover landscape. His tent mate, Shorty, leaned over. “Cheer up, Louisiana’s not really the end of the world—but you can see it from here.”

Harry wiped his face with a grimy bandana. “The only thing worse than your Louisiana mud is your Louisiana dust.”

Shorty—Private Lester Johnson—grinned. “And the only thing that can trump either one is this Louisiana August humidity.”

“At least it’s consistent,” Harry said.

“Yep, consistently miserable.”

Harry spat. “We don’t call it ‘Lousy-anna’ for nothing.”

“How many more days before you leave Louisiana?”

“In seventy-two days . . . ”—Harry glanced at his watch— “twelve hours and about thirty-seven minutes.” The truck turned off into a bone-shaking side road. He stood and scanned the stump-covered field filled with hundreds of tents. “Reminds me of one of those military graveyards with row after row of headstones.”

Shorty nodded. “Looks like they already had a war here, and the trees lost.”

Harry wiped his face with his slouch hat. “This place even feels like a graveyard.”

“That’s why we call this part of Louisiana, ‘No Man’s Land.’”

“Why’s that?”

“It was a neutral strip between Spanish and French territories. It became a hideout for outlaws and anyone else that didn’t want to be told what to do.”

“Folks like your family?”

“Exactly. My family got run out of Alabama, and have been here ever since.”

“You sound proud of it.”

“I’m proud of my No-Man’s-Land-Outlaw-Strip roots.”

Harry surveyed the barren stump-covered fields. “Looks to me like it’s still ‘No Man’s Land.’”

“You hate the Army, don’t you?”

“Probably more than any of the half-million soldiers playing war out here. The only thing that keeps me going is that if I wasn’t here, I’d be in a Wisconsin prison.” The truck jerked to an abrupt halt and a dusty cloud settled over them as the convoy turned east. An enterprising boy was selling newspapers, and one of the soldiers bought a copy of the day’s Lake Charles American Press. Harry’s unit, Company K, comprised of mostly National Guard soldiers from Michigan and Wisconsin, kept a constant betting pool going about whether the Detroit Tigers or Cubs would finish lower in their respective leagues. As the soldiers tore into the sports page, the front section fell to the floor. A soldier retrieved it and began reading out the headlines. The word “extension” caught Harry’s attention.

The reader cursed. “It says here our time is being extended.” Harry tore the paper from the soldier’s hand. There it was in bold headlines: CLOSE VOTE EXTENDS SERVICE TERM FOR THOUSANDS . . . . The convoy began moving as nausea swept over Harry. His worst fears were being confirmed—he was stuck in the Army, and that meant being stuck in Louisiana. This was its own prison sentence. His Army service had gone from days to maybe years. Another soldier, who’d also been counting the days, sarcastically called out their National Guard unit’s motto, “We’ll be back in a year.”

The cussing and bellyaching continued until the trucks pulled into a cutover area that appeared to be their field camp. A soldier whispered, “Here comes trouble,” as Company Sergeant Kickland came around a tent.

A.L. “Red” Kickland, known simply as “Sarge,” loved showing off his stripes. His favorite whipping boy was Harry, who provided plenty of opportunities to serve as a target.

Sarge was short with cropped red hair and a ruddy complexion from which he got his nickname. When he was mad—which seemed most of the time—his face turned crimson. The hot Louisiana sun had further deepened his cooked lobster look. A veteran of the Great War, he prided himself on riding the young soldier whom he considered “soft.” He was loathed by most of the men in Company K.

He stepped to the truck’s tailgate and barked in his raspy voice, “All right, boys, let’s unload.” A blue bandana was pulled over his face for the dust. He lowered his mask. “Welcome to your new home—downtown Fulton, Louisiana.”

Harry grimaced as he jumped down, causing Shorty to say, “That leg still bothering you?”

“Three straight days of twenty-mile marches will do it.” Harry grunted as he hefted his pack. “Especially with sixty extra pounds.”

A new Company K soldier said, “Where’re the hot showers, Sarge?” Harry immediately recognized the accent as from one of New York City’s boroughs.

“Do I look—or smell—like there are any showers around here? This ain’t your Waldorf-Astoria. This is bivouacking at its best.” Sarge’s face flushed.

“Or worst,” Shorty muttered.

The New York private, a skinny Jew named Cohen, jumped to the ground. “Chiggers, we have arrived.” The other soldiers laughed—most had already experienced Louisiana chiggers firsthand.

“Soldier, they call chiggers ‘redbugs’ down here,” Sarge said, “and when they set up housekeeping in your drawers you’ll understand why.”

A veteran of nearly a year in Louisiana added, “New York, you wait ‘til those ticks and mosquitoes start maneuvers on you. You’ll be wishing they were redbugs.”

Harry didn’t see Sarge coming up behind him until Shorty whispered, “Harry, get rid of your gum.” He spit it out before snapping to attention. Sarge hated gum chewing while on duty and could spot a wad from fifty paces. “Miller, what’d you just spit out?”

“Nothing, Sir.”

Sarge walked to the offending wad in a sawdust pile at the base of a climbing wall. “Get down there and pick it up.”

Harry stood over the spot.

“Pick it up with your mouth. That’s where it came from.” Harry glanced at Sarge who stood, arms crossed, feet apart. “You heard me.” Harry scanned the small cluster of Company K men but everyone avoided eye contact. He started to argue, but knew better. He knelt down, put his face in the gritty sawdust, feeling his face redden as he blinked back tears. Being humiliated like this was more than he could take. “Go over in the bushes and spit it out and don’t be spitting gum where we’re walking.” Harry walked slowly over and spit it out and cleaned the sawdust from his mouth.

All the men had left except for Shorty. “Sorry. That was pretty bad.”

Harry glared at the back of the retreating sergeant. “One of these days I’m going to get even with him. I’m going to kill the sorry . . . .” A honking jeep approached from which a driver threw out two sacks of mail. “Mail for Company K.” As soldiers came running, Harry walked away.

“Wait around,” Shorty said. “You might get some mail.”

“None’s coming for me.” Harry had only received two pieces of mail in the past three months, and neither had been pleasant. The first was a letter, which he could still quote word for word:

Harry,

I’ve thought long and hard of how to do this, and there’s no easy way. I’m breaking off our engagement. The truth of the matter is that I’ve fallen in love with John—John Talbert.

I don’t know how this happened, but it did. I hope you’ll understand.

Helen.

Even now, three months later, he couldn’t believe he’d lost his fiancée to the man who’d been his best friend. A month after the Dear John letter, Harry had received a second piece of mail—a small box containing the ring he’d given Helen. No note. No apology. Just the ring.

Still spitting dirt, he sat under a scraggly oak reliving those two painful pieces of mail. The bitterness in his mouth was from more than just sawdust. Shorty walked by. “I got blanked today on mail.” He pulled an object out of his pocket and tossed it to him. “Speaking of blanks, did you know what the guys in the truck behind us were doing earlier?”

Harry held up the .30 caliber cartridge thrown to him. Shorty hesitated. “They were ‘yoo-hooing. Throwing out spent casings with notes inside.”

“That’s against regulations.”

“They were doing it anyway.”

“That’s a good way to get their tail in a crack.”

“You’re right—if the shells contained their names.”

“What do you mean?”

“They were doing it as a joke with other soldier’s names—mainly yours.”

He felt his eye twitching. “What?”

“Yep. Shep threw out a bunch with your name.”

“I am going to knock that blond-headed rascal’s head off!”

Shorty slapped at a cloud of swarming mosquitoes. “Looks like rain.”

“Then it’ll be hot, miserable, and muddy, instead of dusty.”

“Pick your poison, partner.”

Harry spat. “My only comfort was that in seventy-two days, my time was up. Now it’s extended. Just my luck. Extended.” Harry walked to a nearby pile of dried cow manure. As he kicked it, pieces of dried manure flew. The inside was soft and a disgusting green glob stuck to the end of his combat boot. Shorty smirked. “Clean that off before you come into our tent.”

“I hate this God-forsaken place,” Harry said. Deep down inside, he knew something: it wasn’t this place—or even the Army—that made him unhappy. Neither was to blame for his being stuck in the Louisiana Maneuvers.

That responsibility rested on Harry Miller. He had no one to blame but himself.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller