- Scroll down to read today’s story from Christmas Jelly.

Meeting Nelson Mandela on the Damascus Road

It’s big news all over Africa.

Nelson Mandela has died.

“Mandiba” (his African name) was loved by Africans

and rightfully respected by the world.

When I heard of his death, I returned to a lonely windswept section of highway in South Africa’s Zulu country. I went there six years ago. It’s on the road west of Pietermaritzburg.

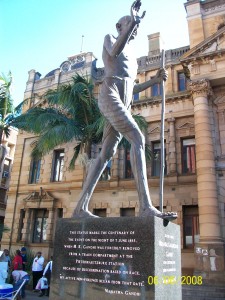

It’s the spot where Mandela was arrested in 1963.

You know the rest of the story. He spent the next twenty-seven years in prison primarily at a place called Robbin’s Island.

I read an editorial from an American theologian reminding us that the young Nelson Mandela was committed to violence and could be considered a “terrorist.” (The writer was kind enough to add that “one man’s freedom fighter is another man’s terrorist.”)

I was also surprised when a younger South African told the BBC, “Mandela let us down as president by not being strong enough on taking land from the whites.” She evidently had no respect for the challenge he faced as president.

I’m not writing to weigh in on where Nelson Mandela was on the scale of right or wrong when he was arrested and sentenced to life in prison. Nor will I judge whether he did enough as president.

I’m more interested in the man who walked out of prison in 1990 completely committed to reconciliation, forgiveness, and peace.

I’d compare that windswept road shoulder to the Damascus Road where another young misguided terrorist had his life changed.

His name was Paul. We call him the Apostle Paul. We don’t judge him by his earlier violence in the name of God. We acknowledge that his encounter with Jesus changed him forever.

I’ve never fully understood Mandela’s personal faith even after reading countless books on him. (I highly recommend Long Walk to Freedom.)

I simply know that somewhere on the journey between his arrest on the road and when he walked out of prison twenty-seven years later, he became a changed man.

He averted a brewing race war in South Africa. He embraced his enemies and captors. He led a new chapter in his country.

For that, and much more, he has my respect.

Rest in peace, Mandiba.

Side note to the above story:

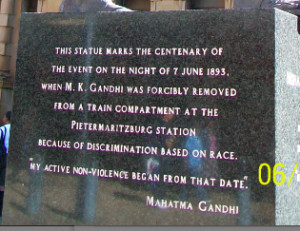

It is more than ironic than another non-violent change movement was born about thirty miles from the spot of Mandela’s arrest.

M. K. Gandhi, at the time a young Indian lawyer, was booted off a South African train in Pietermaritzburg. He offense was trying to sit in the train section reserved for whites.

He said that his plan of non-violent resistance was born at that moment. That movement resulted in the sub-continent of India breaking free from the British Empire.

No Room at the Inn

They say revenge is a dish best served cold.

It was natural—every child in the church Christmas program wanted to be either Joseph or Mary.

Tom was a ten-year-old and wanted the Joseph role in the worst way. Not only did he fail to get the coveted role of Joseph, it went to a rival of his.

Making matters worse, “Mary” went to the love of his life.

As a consolation prize, Tom was cast as the innkeeper. At least it was better than being a sheep or camel. He only had one line. “Sorry, there’s no room in here, but you can stay out in the barn.”

He gritted his teeth through the rehearsals, chafing at the unfairness of his role. He carefully plotted his plan for revenge.

The night of the Christmas program arrived. Proud parents and eager grandparents crammed the sanctuary. Innkeeper Tom, dressed in his bathrobe with a towel and belt headdress, stood behind his cardboard door, ready for his thirty-second role.

“Joseph” arrived with great-with-child Mary, and knocked loudly.

The innkeeper opened the door.

“Sir, my wife is great with child and we need a room to stay for the night.”

But instead of turning them away to the manger, Innkeeper Tom stepped from the door. “Welcome, come on in. We’ve plenty of room.”

His revenge was complete. He’d disrupted the entire play.

Except for one fact: Joseph thought well on his feet.

“All right, let me come inside and look around.”

After ten seconds behind the cardboard door, Joseph rejoined Mary and announced loudly to the innkeeper. “There’s no way I’d let my wife stay in an inn this dirty. We’ll just stay out back in the barn.”

As they say in France, Touché.

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller