Wed. December 7, 2011

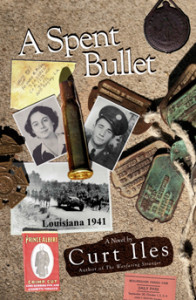

Scroll down to read Chapter Three of A Spent Bullet. It takes place on August 13, 1941.

Part of the tension and hook of A Spent Bullet is that it’s set in the months/weeks leading up to Pearl Harbor.

Harry, Elizabeth, Jimmy Earl, Peg, Sarge and the others don’t know what we readers know: War in coming on December 7. Their lives will never be the same.

It makes you want to shout out, “Harry, get ready. You’re going to war soon!”

It’s Pearl Harbor: 70 years later

A day that will live in infamy. Seventy years ago.

All over America, folks were going about their business on Sunday, December 7, 1941. No one had any idea their worlds would change the next day.

It’s a day we should always remember.

Never forget.

Chapter 3

A Bird Nest

Author’s notes: Chapter 3 of A Spent Bullet deals with a difficult decision schoolteacher Elizabeth Reed is making. Read the chapter and think about difficult decisions you’ve made in your life. How did you make the final decsion? Regrets?

Elizabeth pulled Ben toward the train depot as he protested. “Lizzie, don’t pull on me like a goat at the sale barn.” She had him by the overall strap. “You’re gonna smothercate me.”

Let admit it: I love Ben. I’ve always liked country rascals with hearts of gold.

She rolled her eyes, trying not to laugh. “Ben, that’s not a real word.”

“Smothercate? Ma uses it.”

“Well, just because . . . ” They passed a wall of soldiers crowded around the depot entrance. Safely out of earshot, Ben tapped her arm. “Sister, what’s a ‘real hooker’?”

“Ben Reed. Where’d you hear that?”

“One of those soldiers pointed at you. ‘There’s a real hooker.’”

“Is that what he said?”

“It sounded like it.”

“Could it have been . . . uh . . . ‘a real looker’?”

“I thought he said ‘hooker.’”

Elizabeth tousled his hair. “Ben, a ‘real looker’ is, uh, a good-looking woman.”

“Like you?”

She laughed. “I don’t know about that. But a hooker? It’s a bad name for a bad girl. It’s not what you want your sister called.”

“You want me to go back and whup him?”

“No, we’ll let him go this time, but thanks anyway.” She hugged him. The little rascal was her favorite person in the world.

Ben stopped in front of the uniformed men piling off the train. “Where are they coming from?”

“From furloughs up north or arriving for new assignments here.”

A skinny soldier bumped into her. “I’m so sorry, Miss.” He removed his cap, but his smirk remained. “Where are you going?”

“As far away from you as possible.”

The soldier turned to Ben. “Here to meet someone, little man?”

“Nope, we’re here to get something.”

Elizabeth coughed. “Let’s get to the freight landing.”

“Do you see our crate, Sister?”

“Not yet.”

Ben dug into the middle of the stacked boxes. “I hear them but can’t see them.” Elizabeth moved to the chirping crate. He pulled on her dress. “Are they still alive?”

She peered through the slats. “Looks like they are.” Suddenly, someone grabbed her from behind, loudly crowing in her ear. It couldn’t be anyone but her sister, Peg.

“We about gave up on you.” Elizabeth eyed her carefully. “I figured you were flirting with some soldier.”

“What do you mean soldier? I was flirting with an entire platoon. You ought to try it sometimes.”

Ben interrupted them, holding up the crate. “Did they really come all the way from Arkansas?”

Elizabeth peered through the slats at the chirping baby chicks. “All the way from DeQueen, Arkansas.”

Ben stooped to see. “From DeQueen to DeRidder.”

The chirping biddies attracted plenty of attention in the depot, causing her to walk faster. The same tall soldier blocked her path. “So you’re a chicken farmer?”

“Well, if I am, you’re not my kind of rooster. Goodbye and good day.”

The soldier raised his hands in mock horror as Ben, fists balled, stepped between them. “Fellow, I believe you could wart the horns off a brass billy goat. Leave my sister be.”

The soldier turned toward Peg. “And who’s this pretty country girl with you?”

Ben stood his ground. “She’s her twin sister and you can leave both of them alone.”

“They sure don’t look like twins.”

“They’re that other kind of twin.” He scratched his head. “Ma—that’s my grandma—says those kind of twins come from—” Both sisters grabbed at him as Peg said, “Ben Reed, Momma said she was going to beat you into next week if she heard you say that again.”

Elizabeth hurried her little brother out of the depot back to their street corner, set the crate down, and pulled out two nickels. “Would you like a Coke and snack?”

He punched the air with a fist. “Can I get something now?”

“We’ll watch the biddies until you get back.”

Peg watched him run off. “I love people’s faces when they find out we’re twins.” She touched Elizabeth’s arm. “You and your dark hair and skin and me with enough freckles to cover the moon.”

“You’re just fine like you are.” Elizabeth mushed her sister’s strawberry blonde hair. “Even if you do look like you just got off the boat from Dublin.”

“I’m not the one the guys look at—you are,” Peg said. “It’s those dark mysterious eyes and your olive complexion, Squaw.”

Elizabeth shot back. “Mick.”

“Redbone Woman.”

“Colleen Blarney.”

“Injun.”

The war of words continued until a jeep driver honked his horn and yelled, “Hey, kid, get out of the road.” Elizabeth spun to see the jeep stopped in front of Ben, who was contentedly holding his Coca-Cola and bag of shelled peanuts. The driver motioned him to the sidewalk. “Son, you’re gonna get run over.” He turned to Elizabeth. “Ma’am, you’d better watch your—”

“He’s my brother.”

“Well, you’d better watch your brother.” He winked at Peg and peered at the crate. “Got some new biddies?”

Ben walked to the jeep, which had 1931 painted boldly on its hood. “How’d you know we had biddies?”

“First of all, I can read. ‘Baby Chicks. Handle with Care.’ Besides, I was raised on a farm in Moline, Illinois.”

Ben clapped his hands. “Moline? John Deere country.”

“Home of the world’s best tractors.”

“Hey, your jeep number—1931—is the year I was born.”

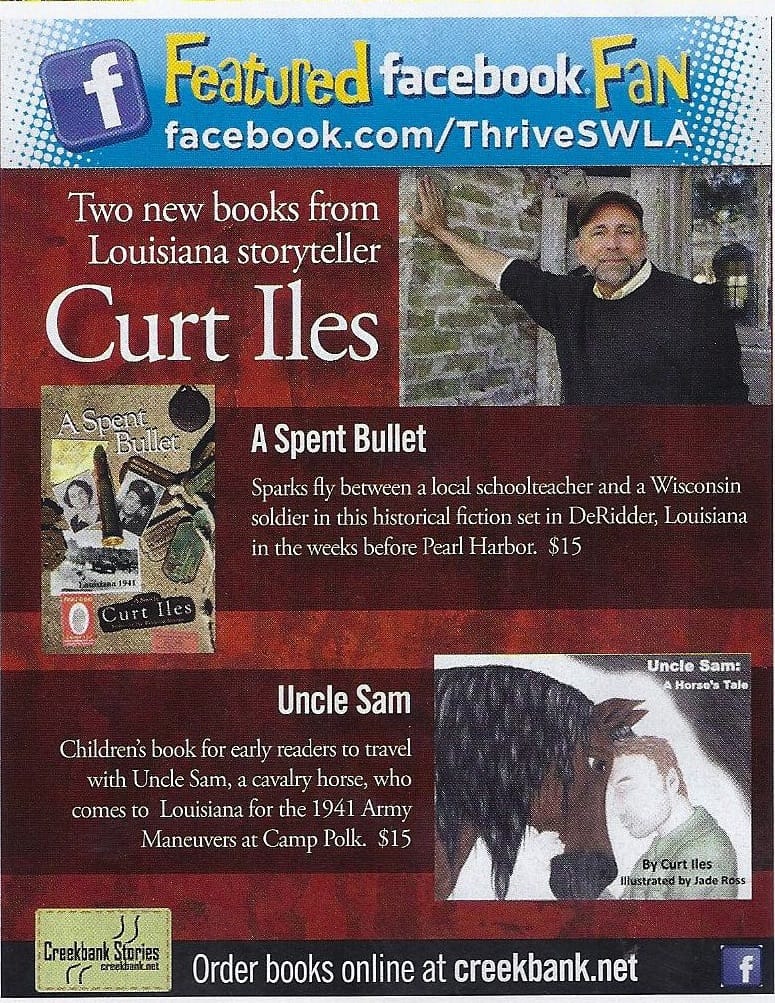

Author’s note: Jeep 1931 is also shown in our children’s book, Uncle Sam.

“No joke. I guess that makes you, uh, about ten years old.”

Another jeep honked. “Come on, Lawrence. Get moving.”

The driver saluted Ben. “Gotta go. Stay off the road and take care of your biddies.” He looked past Elizabeth at Peg. “I hope to see you around.”

Ben waved. “See you later.”

“You might if you stay off the road.” The driver winked. “You’d better keep an eye on him.” He expertly gunned Jeep 1931 between two large trucks in the convoy and sped off.

Elizabeth turned to her sister. “You were the one he noticed, not me. Did you know him?”

“I haven’t the slightest.”

“The slightest what? You can’t end a sentence with an adjective.”

“I can if I want to.” Peg pursed her lips. “Slightest, slightest, slightest.”

Elizabeth nodded at the disappearing jeep. “He noticed you.”

“Well, even a blind hog will find an acorn every blue moon or so,” Peg called over her shoulder. “I’m going to do some shopping at Morgan and Lindsey.”

Ben, washing the peanuts down with a big swig of Coke, said to Elizabeth, “You know, you’re my hero.”

“Because I bought you a Coke and peanuts?”

“No, ‘cause you take good care of me.”

She hugged him. “Ben, promise me that you’ll watch for traffic.”

“I will.”

“You stay here and guard the chicks while I’m at the post office.” She hurried to the postal building where she’d recently opened a box for her private correspondence. Slipping her key into the box, she pulled out two letters, scanning their return addresses. The first one was in a small envelope with no forwarding address. She ripped it open and read in Dora’s familiar script.

August 10, 1941

Shreveport, La

Elizabeth,

As promised, I’m reporting to you on Bradley. I saw him last week at church, and he looks truly happy.

Also, I’ve told no one. You can trust me.

Sincerely,

Dora

Her hand trembled as she re-read it. Bradley. Happy. She glanced around the post office hoping no one saw her tears. She wiped her eyes and read the legal-size envelope, stopping at the typed return address:

Caddo Parish School Board

Shreveport, La.

Ripping open the envelope, she read the first paragraph:

Miss Reed,

We are pleased to offer you a job as an elementary teacher at Byrd Elementary School for the coming year of 1941–42. A contract is enclosed for your signature.

She dropped both letters and clutched her stomach. What I’ve dreamed of is in reach. A new life one hundred fifty miles north . . . but why do I feel like . . . like it’s a poor decision? What’s wrong with me? I always have to make everything so complicated.

“Miss, Miss—you dropped your letter.” An older woman handed her the letters. “Are you all right? Bad news?”

“No, Ma’am. It’s great news.” She gathered the letters. “Great news.” Elizabeth hurried out of the post office. A great pay raise, in the city where she’d always longed to be. Where her heart was. Bradley. Why did such good news sadden her?

She hurried to the Beauregard Parish School Board Office. School was slated to begin in two weeks. A rumor had been circulating that opening might be delayed due to the Army Maneuvers. She entered the building and found a secretary. “I’m checking about the start of school.”

“You haven’t heard? The Board met last night and postponed school until the first Monday in October.”

“That’s official?” Elizabeth felt her heart quicken. The Caddo Parish letter in her pocket seemed to be calling her name.

The secretary nodded. “It sure is. Soldiers are camped on school grounds, and it’d be dangerous running buses among the military traffic.”

“First Monday in October?”

Starting school in 1941 in SW and Central Louisiana was delayed until late September or October. I’ve been told some schools went on Saturdays while others went later in May.

She glanced at her desk calendar. “Looks like October 6 to me.”

“Will we still get paid?”

“Teachers will, but support personnel won’t.”

Elizabeth frowned. Her father’s school bus route supplemented his work at the sawmill. A month without bus pay would knock their family for a loop. She hurried out in a daze, quickly forgetting about Poppa’s bus salary. She had a difficult decision to make. Lord, help me know what to do.

She hurried to the street corner, slipping behind Ben who was counting a column of passing cavalrymen. “Thirty, thirty-one—I’m gonna ride one of those horses even if it harelips the pope.”

“Ben, don’t talk like that.”

He spun around in surprise. “I about gave up on you.” He hooked his thumbs in his overalls. “A dollar waiting on a dime.”

As the last mounted soldier saluted, Ben jerked his hand out of his pocket to return the salute. As he did, his harmonica clattered to the sidewalk, but that wasn’t what caught Elizabeth’s attention. It was the five-dollar bill that fluttered beside it. She scooped up the bill, waving it in front of his face. “Benjamin Franklin Reed, where’d you get this?”

“I found a bird nest on the ground.”

“You what?” She knelt in front of him. “Is there more?”

“Not a five, but I got a whole pocket full of ones.”

“Show me.” He emptied both pockets plus the snap on his bib overalls, piling the crumpled-up dollars and coins on the sidewalk. She stammered, “Who’d you take that from?”

“I didn’t take it. It came from selling them cokes.”

“What cokes?”

“I sold the coke you bought me to a thirsty soldier for a whole dollar. Then I bought some more and sold them to the convoys.” He pointed at the small mountain of wadded bills. “That’s how I got it.”

“You sold nickel cokes for a dollar each?”

“Yep, and they were as happy to get ’em as I was to sell ’em.” He stepped back as if he knew what was coming. “Uh-oh. Looks like something’s rotten in Denmark.”

“Now, listen here, Shakespeare—selling a coke for a dollar. That’s—why, that’s highway robbery.”

Ben looked back toward the street corner. “Lizzie, it wasn’t highway robbery. It was right here on First Street.” He stood proudly. “Yep, I found me a bird nest on the ground. Right here in D’Ridder, Louisianer.”

Elizabeth wasn’t sure if she should spank him now or wait until they got home. “How’d you get a five-dollar bill?”

“A truckload of soldiers gave it for a whole case of Cokes.” He shuffled his feet. “When I got back, they were gone, so I sold them to the next truck.” He watched her scoop up the money. “It’s enough money to burn a wet dog, ain’t it?”

“That’s more money than your daddy makes in a week at the sawmill.” She gritted her teeth. “Momma’s going to burn your wet dog when we get home.”

He shrugged. “Sounds like something’s rotten in . . . DeRidder.” Elizabeth groaned. Sometimes he was more than she could handle. It was going to be a long school year . . . if she stayed. Elizabeth stuffed the money into her purse, feeling for the two letters. It would be a difficult decision, but Shreveport was her bird nest on the ground. This was what she’d dreamed of—living in a city away from the difficulties of rural life. She’d prayed for this opportunity.

Why then did she feel so reluctant about going?

What’s the most difficult decision you’ve ever made?

These excellent discussion questions are from my lifelong friend Don Brewer. Help us add more.

- Why does Elizabeth have such affection for her little brother Ben?

- In this chapter, Elizabeth’s fraternal twin sister Peg is introduced, why do you think Lizzie and Peg are so different in appearance and disposition?

- Who do you think Bradley is, and why did Elizabeth weep when she found out he was happy?

- Why is Elizabeth so torn about moving to Shreveport and teaching?

- Do you think Elizabeth’s thoughts “Lord, help me know what to do” are a real prayer or just a random thought?

- In Southern speak – what emotion does using someone’s full name to address them imply, (e.g., “Benjamin Franklin Reed, where’d you get this”)?

- Why is Elizabeth upset with Ben for making a profit (gouging) the soldiers for a coke?

- The phrase “finding a bird’s nest on the ground” is used twice in this chapter, what do you think it means?

- What does the phrase “burn your wet dog” imply?

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller

Creekbank Stories Curt Iles, Storyteller